- Home

- Howard Jacobson

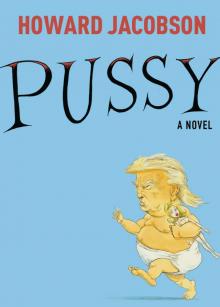

Pussy Page 10

Pussy Read online

Page 10

‘You get money for shopping your friends,’ he explained. Already he had assumed the menacingly soft tones of the Master of Betrayal.

‘Is that it?’

‘And people shout “spravchik”.’

‘Spravchik?’

‘Spravchik.’

On hearing this word, the driver of the limousine swung round in his seat. ‘You know Spravchik?’

Dr Cobalt looked at Professor Probrius. They were both accomplished linguists, but no, neither of them knew what spravchik was.

‘Spravchik is not a what, he’s a who,’ the driver called over his shoulder. ‘Vozzek Spravchik is our Foreign Secretary.’

‘Why, in that case, would people have been calling out his name on a game show?’ Probrius asked.

‘Why? Why not? It’s his show. They were calling for him.’ Cheem, they were calling for cheem, he pronounced to the Prince’s delight. Setting aside Gnossia, where people spoke the same language he spoke, Fracassus had never left Urbs-Ludus and had not heard a foreign accent before. His genius for mimicry was tickled. Cheem, he kept saying to himself. He added it to his repertoire. Lordy, lordy; the floppy-limbed spastic bedmaker, and now cheem. A comic routine was taking shape.

Probrius did know something of the world beyond the Republic, but he was still surprised by what the driver told him. ‘Your Foreign Secretary is a game-show host? Is there not a conflict of interests?’

‘What conflict? He is also Minister of Home Affairs, and Culture Secretary. Why not? No conflict.’ Confleect.

A thrill went through Fracassus. Confleect. Chwy not. Cheem. Life had become very amusing suddenly. If only he had an audience bigger than Probrius and Cobalt to amuse. An audience the size of the one that had watched him knock out the subversive singer. Spravchik!

The next day, following a morning of sightseeing in which Fracassus saw nothing, Vozzek Spravchik invited the Prince and his little party to meet him at the Ministry. The plan before they’d left home had been for Fracassus to travel this leg of the journey incognito, without the hindrance of diplomatic nicety and protocol, but he had been so insistent in his desire to see the Minister in the flesh, that messages had been hurriedly exchanged, permissions sought, and here they were.

To Fracassus’s disappointment, the Minister greeted them in an ordinary lounge suit and without his assistant from the show. He could have been a civil servant. But then he took his tie off and spiny black bristling hairs, that reminded Fracassus of a wild boar he’d seen on a natural history programme, sprang from his shirt. A pungent smell came off him. On the walls of his office were photographs of Spravchik in his swimming trunks, driving a jeep, diving, surfing and standing in an Olympic pool balancing on each shoulder the two synchronised swimmers who’d won silver medals for their country in the recent games. There were also two life-size paintings in the heroic style – one of him arm-wrestling a polar bear and the other of him gently removing a thorn from a lion’s paw. ‘These are the two sides to my personality,’ he explained. Fracassus’s initial disappointment in the man dissolved in his admiration for the art.

‘Welcome, anyway, to you all,’ Spravchik proclaimed, as though to a vast gathering, extending a hand to each of the party in turn. ‘There are, I hope, no hard feelings left between our peoples. Sometimes you have to have enemies to know who your friends are.’

Though Fracassus was not aware there’d been hard feelings between the Republic of Urbs-Ludus and Cholm, he liked Spravchik’s verbal style and wanted to show he could match it. ‘And sometimes you have to be right to be wrong,’ he responded.

Spravchik appeared delighted by this and clasped Fracassus to his strong chest. ‘We should wrestle,’ he said.

Professor Probrius wasn’t sure that was a good idea. The Prince had only recently got off a long-haul flight and was no doubt suffering jet lag.

‘And I have just knocked someone out with my fist,’ Fracassus added.

The Minister roared his approval. ‘Show me how you did it.’

‘Not a good idea,’ Probrius put in, fearing another diplomatic incident. ‘Perhaps in a few days, when the Prince is recovered, Minister.’

‘Just name the day. That will be beautiful. I have a full-size wrestling ring.’

‘That is an occasion we all look forward to,’ said Dr Cobalt.

‘Looking forward can be dangerous,’ said Spravchik, ‘but not as dangerous as looking back.’

Fracassus decided against trying to match his verbal style again. ‘How long have you been doing your show?’ he enquired instead.

‘Is a question I am always asked: which came first, your political career or show business? Chicken/egg, egg/chicken. I say they came together. What’s the difference? The people love my show and vote for me. The people vote for me then watch my show. Trust the people. They don’t make the false divisions intellectuals do. Whoever touches the soul of the people embraces truth. The people sometimes need guidance but they are never wrong. The people are beautiful. You want tickets?’

Probrius and Cobalt were about to shake their heads but Fracassus nodded his.

‘We are recording this evening. You must come. All of you. I will get you tickets. Never put off doing until tomorrow what you can do today – and that includes invading your neighbours …’ He paused to measure his effect. ‘Only having fun with you,’ he went on.

‘Sometimes fun can be mistress to a not-so-funny deed,’ Professor Probrius said, though the moment he said it he couldn’t understand why he had.

Nor could Minister Spravchik. He narrowed his eyes and showed his teeth, much as he did when offering a contestant money to betray his best friend’s political affiliations to the secret police. Professor Probrius started from the steely light. Fracassus felt drawn into it. This was the first great man he had ever encountered face to face. Compared to Spravchik, Philander and Hopsack were minnows. And Eugenus Phonocrates was dead. ‘Yes, please,’ he said. He had a new word and wondered if he had the courage to use it. ‘Tickets would be beautiful.’

‘It takes great faith to ask,’ the Minister said, clasping Fracassus to him again. ‘And it takes even greater faith to give. I am guided by my faith in everything I do. I have so much faith in me you can hear it beating against my ribs. No man has more faith.’

Fracassus listened and could hear it. He had promised his mother he would write and now he knew what he would say. ‘Dear Mother, I have just held genius in my arms. Don’t worry. Not a Rationalist Progressivist. Not a hooker either. Your loving son, Fracassus.’

That night he sat in the front row of Whistle-Blowers and when the crowd rose to bait the faint of heart, so did he. ‘Spravnos!’ he shouted.

Professor Probrius also planned his email to his employers. ‘We have barely been away three days but already Fracassus has won the hearts of all Gnossians, and is now further extending his understanding of foreign customs,’ he would write. ‘He is winning friends and forging new alliances wherever we go. The honour he is lending to the name of Origen is all you would have wished for.’

Lying in Yoni Cobalt’s arms he whispered, ‘Spravchik.’

The Doctor jumped up. Many were the hours and long were the nights through which she’d lain in a fever of desire, imagining just such a moment as this – she and Kolskeggur alone in a foreign place, listening to the howling of the wolves, far from television and the Internet, every minute before dawn theirs to do with as they wanted. And he had chosen to whisper ‘Spravchik’ in her ear. What did he mean by it? Was he playing some perverted jealousy game? Was he one of those men who needed to feel rejected before he could feel loved? ‘I’m not turned on by Spravchik if that’s what you’re trying to find out,’ she said.

‘I should hope you’re not,’ Probrius said. ‘Neither am I. But it would appear our little Prince is. For a supposed tough guy he’s easily swayed by other tough guys, wouldn’t you say?’

‘What are you implying?’

Professor Probrius laughed. He did

n’t know. That the boy was dangerously susceptible to muscularity, that was all.

Yoni Cobalt saw it as the Prince trying out what sort of man to be. He’d been groomed to greatness. But what kind of greatness? It was up to them, wasn’t it, to show him other ways than Spravchik.

Kolskeggur Probrius kissed her fondly. ‘You want to make a good man of him, do you? Who are your models? Jesus? Gandhi? Doesn’t he own too much property to make it into their league? You can’t grow up on a Monopoly board and hope to direct others how to live nobly.’

‘You can if you discard the Monopoly board.’

‘And the television.’

‘Yes, and the television.’

‘And the Internet.’

‘Yes and the Internet.’

‘And the social media.’

‘Yes, definitely the social media.’

‘And then there’s abnegation of the ego.’

‘So we’ll leave him to Spravchik, then?’

They went to sleep thinking their own thoughts. Not for the first time, Probrius felt that if he could only stay patient things would work out nicely in his favour. Fracassus a saviour? Hardly. Fracassus a scourge, more like.

He listened to what the wind was saying, and it agreed with him.

Minister Spravchik would not hear of Fracassus and his party leaving just yet. He put a super-stretch government limo at their disposal, together with an interpreter and a guide to the country’s monuments and museums. Just as the car was about to pull away he ran out in front of it, waved it down, and jumped inside. He was wearing a tracksuit in the colours of his country and a bobble skiing hat. ‘You two can get lost,’ he told the interpreter and the guide, pointing his thumbs back over his shoulder.

Fracassus added another expression to his collection. You two can get lost. And then the thumbs. He’d use that one day.

‘What I think we’ll do first,’ Minister Spravchik told them, pouring himself a slivovitz from the limo’s cocktail cabinet and knocking it back in one swallow, ‘is go up into the Blackbread Mountains where you will be able to see indigenous handicrafts being made and taste the local brew. Then if there’s time we’ll go back down into the White Canyon and do the same.’

He foamed with laughter, which Fracassus reciprocated.

The colour went out of Spravchik’s face. ‘The idea of meeting indigenous people amuses you?’

‘No,’ Fracassus said. All the colour that had fled Spravchik’s face flew into his. ‘I thought it amused you.’

‘Why would it amuse me? I am Culture Secretary. The welfare of our most ancient and poorest inhabitants is of the first importance to me.’

They drove into the mountains in silence. Fracassus had never been into mountains before. But he couldn’t look around him. He was too upset.

Spravchik’s mood, however, appeared to improve. ‘Come,’ he said, when the car stopped at the summit. ‘First we enjoy the view – the greatest in the world. Then we watch the ceremony of the threading of the beads. People have been practising the art of bead threading on this very spot for hundreds of thousands of years. They mine the quartz from the mountain, shape them with flint stones, drill holes through them with a sharpened dogwood stick which they rub between their hands – a method unique to Cholm – then string them on ropes made from the wild vine liana. Come. Look.’

Sitting outside a rough habitation were a dozen of the saddest, blackest individuals Fracassus had ever seen. They appeared to have been staring vacantly into space until the party wandered over, whereupon they bent their heads industriously and began the drilling.

‘It must hurt their hands to do that,’ Fracassus said. He wanted to show what a great interest he was taking in the indigenous customs of Spravchik’s country.

‘Not any more,’ Spravchik said. ‘They were doing this when you were still a bacterium in the belly of a wriggle fish. Here’ – he seized a finished necklace of beads from a woven basket and hung it around the Prince’s neck – ‘a gift from the Numa people. Now we’ll go over to witness the fermentation ceremony and have a drink.’

Fracassus fingered the beads and got immediately drunk.

‘Strong, huh?’ Spravchik said, enfolding Fracassus in his arms.

‘You?’

‘The drink. We’ll make a man of you before you leave us … Unless I can persuade you to stay. Will you?’ (It was the same low serpent hiss Spravchik used to persuade contestants to sell their sisters for sixpence.) ‘Say yes. We could invade a country together. I’ll let you pick one. What do you say, Professor Probrius? Can I have him? And you, Dr Cobalt? Your role is the mother’s, I presume. Can you bear to part with him?’

There was much mirth and saying ‘If only’, but it was impossible to know if the invitation was genuine.

On the road down from the mountain Spravchik continued to enthuse about the Numa people and their customs. But the moment they were back on flat land he began to inveigh against their laziness, their alcoholism, the tawdriness of what he called ‘their shitty little customs’, and the cost to the exchequer of keeping them in welfare.

The party fell quiet. Fracassus because he was asleep, Professor Probrius and Dr Cobalt because of who they were.

‘I know what you are thinking,’ Spravchik said to Dr Cobalt whom he had picked from the start as subversively liberal.

‘I’m not thinking anything, Minister, except how beautiful your country is.’

‘I appreciate your flattery but I know your culture and I know you are wondering how I can praise the peasants when I am among them and wish to exterminate them when I am not.’

‘I hadn’t thought you wished to exterminate them, Minister,’ Dr Cobalt said.

‘There you are. That’s the very judgementalism I was referring to. Exterminate is just a manner of speaking. I could as easily have said “remove” or “relocate”, but I wanted to provoke you into outrage. And I have succeeded. Allow me to say that you don’t appreciate the complexity of holding several conflicting portfolios simultaneously. I have to be all things to all people in this country. On the mountain I am Culture Secretary. Down here I am Minister for Home Affairs.’

Fracassus had woken up. ‘And you are beautiful as both,’ he said, slurring his speech.

As was the custom in Cholm, Minister Spravchik kissed him on the mouth.

CHAPTER 18

In which Fracassus almost reads a book

Picture the emotions warring in the chest of young Fracassus. Word of his fame as the hero of Gnossia reached him intermittently. Cholm was mountainous and the signal erratic. He tweeted his thanks to his admirers but couldn’t be sure they ever reached them. This was the wrong place to be at such a time. It was as though the world was celebrating his birthday without him. But didn’t Spravchik’s company compensate for this? He wasn’t sure whether to be flattered by Spravchik’s friendship or miffed that Spravchik wasn’t adequately flattered by his. Did Spravchik always mean what he said? Where, for example, was the promised wrestle?

But the most perplexing question of all concerned heroism. Could one be a hero and a hero-worshipper?

To the best of anyone’s knowledge, that’s to say to the best of his own knowledge, Fracassus didn’t dream, but he was getting perilously close to dreaming of Vozzek Spravchik. He felt spurred to emulation but somehow diminished at the same time. Was heroism a virtue one could forfeit in the act of admiring it in others? He would have liked to discuss this with his father, but his father was far away. This left only Professor Probrius, whom he didn’t like and after more than half a dozen words couldn’t follow, and Dr Cobalt, but Dr Cobalt was a woman. Could a man – should a man – discuss heroism with a member of the very sex heroism existed to impress?

He decided he would raise the matter with her casually, much as he might raise the matter of a missing shirt. Just by the by, did she happen to know of any blog or vlog or YouTube video on the subject of heroism? She wondered why he wanted it. She ventured to hope he hadn’t

gone overboard on Spravchik.

‘Overboard?’

‘Well, he is what many would regard as a heroic figure and I can see that you respect him.’

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘There’s nothing wrong with respecting any man so long as he is worthy of it.’

‘And you think Spravchik isn’t? Is that because he drinks?’

‘Not just that. The man has an appalling human rights record.’

‘Because he arm-wrestles bears?’

‘No, I wouldn’t call arm-wrestling a bear a violation of human rights. Though it might violate animal rights.’

‘What if the bear wins?’

‘Good for the bear, but the gay and lesbian people he imprisons and the women he flogs for having abortions won’t be consoled by that.’

Fracassus allowed his mouth to fall open. There was an unwritten code at the Palace as to what did and did not constitute appropriate conversation between a prince and his tutor. There were grey areas but abortion wasn’t one of them. As for any sexualities other than heterosexuality, no mention was permitted of these either after Jago’s dereliction. Had foreign travel caused Dr Cobalt to forget herself?

She asked herself the same question. ‘I apologise if I have offended you, Your Highness,’ she said. ‘I thought you were asking my opinion.’

‘Your opinion! When I want an opinion I ask a man.’

‘In that case might I suggest Bear Grylls’ Spirit of the Jungle. I’m told it’s a stirring adventure story.’

Story! Fracassus shook his head in frustration. Spirit of the Jungle sounded like the stuff his mother had tried to force on him. Spirits, fairies, fantastic beasts. What would Spravchik think of him reading a story about animals you couldn’t wrestle because they weren’t really there? He pushed his face out at her. ‘I don’t want fake-fiction,’ he shouted.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights