- Home

- Howard Jacobson

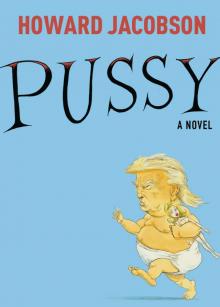

Pussy Page 12

Pussy Read online

Page 12

‘Is it wrong to identify a source?’

‘It is wrong to spread the net so wide that the source becomes an entire people.’

‘How else, in a liberal democracy, are we to set about stopping it from happening again?’

‘Increased security. Detective work. Intelligence …’

‘And if they fail?’

‘We have to try making the world a better place.’

‘And in the meantime?’

‘Act humanely.’

‘And that means sympathising with the terrorists.’

‘If it was terrorists who did it.’

‘Oh, come on, Yoni, they’ve claimed it.’

‘Ah, so now you trust them?’

‘Ah, so now you don’t?’

Fracassus, who had been attending to every word between them – it was the longest conversation he’d ever listened to from start to finish – tweeted underneath the table: Liberal democracy equals more sympathy for bombers than for bombed.

CHAPTER 21

The loneliness of the braggart

Never was a truer word spoken: A prophet is not without honour, save in his own land.

Far from his native country, where he had grown up in the shadow of his father the Grand Duke, Prince Fracassus was attracting attention for his ability to attract attention. With each new tweet and exploit another clipping was added to that collage of moral force and popular influence known to an age of rapid dissemination of trivia as personality. After his heroics at Gnossia, stories of the temple he was building in Cholm began to appear on message boards and news sites. A photograph of Cholm’s Chief Minister, Vozzek Spravchik, anointing him with Numa oil high in the Blackbread Mountains with nothing but a drop into black infinity behind them, and soft round clouds like women’s buttocks floating above, appeared again and again in celebrity magazines and colour supplements. Only an official selfie of the two men toe-wrestling in the barren Makindo Desert as the sun went down received more coverage – though that mainly in magazines for men who liked looking at photographs of men.

When his tweets on the subject of the Plasentza bombings appeared it was as though the prayers of thousands had been answered. The country did not lack for information and opinion. A liquid crystal display device in the hands of every citizen facilitated the transmission of all conceivable views on all conceivable subjects. Anything that could be said, had been said. But the digital context was everything: no one, especially in a liberal democracy such as Plasentza, wanted to see their thoughts or secret beliefs replicated word for word on a hate site. Young himself, and photogenic in the sense that people were becoming accustomed to his image, Fracassus made available to the under-thirties what until now only the over-fifties had thought. By virtue of the family he came from, the title he held and the size of his property portfolio, he lent centrality to opinions hitherto only heard on the lips of disreputables and drunks. Though he could no more have strung his random vociferations into a system than he could have read a sentence of Thomas Carlyle on hero-worship, others had begun to marshal and codify everything he said for him. To those who argued that it hardly amounted to a political programme, others argued that it did. Does/doesn’t was the stuff of Twitter and kept Fracassus’s name before the public.

Occasionally at first, but with growing frequency, word of what he was saying leaked out of Plasentza back to the Republics. It began to be invoked in the course of those yoga-mat demonstrations which had been no more than a minor inconvenience for traffic at the time Fracassus left Urbs-Ludus, but had since grown into a serious threat to the stability not only of Urbs-Ludus but to All the Republics. ‘Where is Fracassus?’ was a call heard first on this side of the Wall, and then on that. ‘Who is Fracassus?’ the Prime Mover of All the Republics was reported as enquiring. Though whether in fear of his influence or in expectation of his support no one could be sure.

Outside the Palace of the Golden Gates, few had known of Fracassus in his youth. He had not been allowed out into the world much. Brightstar intermittently championed him, but so ironically hyperbolic (unless it wasn’t) had been their coverage that for every enthusiast they won to his cause, they lost a dozen. Now he was somewhere else, theories as to his true identity proliferated. He was an invention of a news-starved media. The House of Origen, having been shaken, first by the rumoured scandal of a sex-change heir, then by the demonstrations outside their properties, had come up with a manufactured robotic figure to mend their fortunes. Fracassus was a charlatan, a chimera, a ghost, a bankrupt. By the same token he was a businessman who turned to gold leaf everything he touched, an architect of wild dreams, a patriot, a hero, and an orator of genius.

That all this made him the ideal person to be given his own television show could not be disputed when the idea was floated to the Head of Celebrity at Urbs-Ludus Television. The word went out. Find him. Bring him back. Offer him anything.

But no one said ‘immediately’, so there seemed to be no hurry.

‘Our boy is shaping up,’ the Grand Duke told his wife.

‘What as?’

‘The thing we always wanted him to be. And quite frankly, if you take a look at what’s happening on the street, the thing we need him to be.’

‘I’m a mother, Renzo. A mother only wants her son to be happy.’

‘He can be happy and great.’

‘I still see his face on the day he left.’

Knowing his wife’s aversion to their son’s looks, the Grand Duke doubted that. ‘Describe it to me.’

‘He looked so sad.’

‘It’s good for someone his age to suffer disappointments.’

‘Renzo, his whole world came crashing down.’

‘He’d only known the girl ten minutes. I’d call that a brief disenchantment. Brief, but necessary.’

‘You seem pleased it happened.’

The Grand Duke rose from his chair and paced the room. He did not like concealing things from his wife. ‘My dear Demanska,’ he said, ‘I am pleased it happened and have no regrets that I made it happen. At the time he left us, Fracassus was, for all his stubbornness of character, a clay man. A person had only to graze him with their thumb and it left an impression that lasted for a month. It struck me as best to get some impressions over and done with while he was still young. I feel wholly vindicated by the figure he is cutting in the world right now.’

‘You made it happen?’

‘I did.’

‘You hired a girl to break my son’s heart?’

‘Demanska, our son doesn’t have a heart.’

‘You actually paid someone?’

‘Sojjourner, yes. I auditioned actresses but none could quite manage the self-righteousness. It turns out that only a Progressive Metropolitan Elitist can convincingly play a Progressive Metropolitan Elitist for money. I wanted Fracassus to fall for her and fall for her he did. I wanted him disillusioned and disillusioned he became. Now look at him. I made him so Progressive-proof that even Reactionaries start from his pronouncements.’

‘And you know for sure the girl is not in his life somewhere?’

‘They wouldn’t last ten seconds in each other’s company today.’

‘Then I wonder who is in his life?’

‘Ambition.’

‘How lonely he must be.’

‘You’ve forgotten how much he enjoys his own company. A vain man is never lonely. Which is a good job because a braggart never has a friend.’

‘My poor Fracassus. How cruel you’ve been to him, Renzo.’

‘Only to be kind, my dear. Only to be kind.’

He didn’t tell her that the Head of Celebrity at Urbs-Ludus Television had been enquiring as to Fracassus’s availability and mentioning eye-watering sums of money. Bearing her sensibilities in mind, he did suggest they think about giving Fracassus a book show, an idea they said they’d consider, though in such an event the fee would not be so eye-watering.

CHAPTER 22

In which the Prince forms an even high

er estimate of his gifts

International communication having reached a level of sophistication and celerity unknown to previous ages, word of what the world was thinking of Fracassus reached him almost before it thought it. He would not have been human had this not moved him to what in a lesser person might have been called conceit, but in him passed as confirmation of abilities hitherto gone unremarked.

The bomb, he found the modesty to confess, had quickened his maturity. I have gone from boy to man in a single morning, he tweeted.

Within the week, newspaper supplements were carrying the story HOW A BOY BECAME A MAN, alongside photographs of mangled corpses. These he no sooner saw than he retweeted, and so there and back around the globe the message went as though it were the media equivalent of perpetual motion.

In the bomb, Fracassus saw – that is to say Professor Probrius taught him to see – not only his opportunity but a truth that offered opportunity for everyone. Society had grown degenerate. It had lost the ability to draw a distinction between the guilty and the innocent, it had lost the courage to blame, it had taken ordinary decent outrage and turned it into bigotry, it had made good people fear the consequences of their goodness. Bombs only kill when we’re scarred to kill the killer, he tweeted.

That should be scared, Professor Probrius told him. But it was too late.

Bombs only kill when we’re scarred to kill the killer was re-tweeted more than a million times. Scarred was considered a master stroke, enmeshing in a visual, an auditory but, most important of all, a consequential way, the concepts of fear and wound, cowardice and disfigurement, the momentary and the never-to-be-forgotten. That which scared us scarred us. That which scarred us marked us out as scared. We who were afraid to condemn the bombers were also victims of their bombs. But where other victims died, we were only scarred, which made our being scared the more ignoble. Or was there something holy in our refusal to kill? Scared was an anagram of sacred, the anagrammatising clue being the verb to scar. Disfigure the word for afraid and we got the word for righteous.

There was no end to the play people could make of this mistake of genius.

‘He’s claiming it as his, I suppose,’ Dr Cobalt said.

‘He’s trying to,’ Professor Probrius replied. ‘But he isn’t quite sure what it is he’s done. He came across the word anagram in a tweet the other day and had to put himself to bed. He’s going in for a lot of jutting and pouting which is the usual sign he’s bluffing something out.’

Whether Fracassus was aware of what he’d done or not, his name now hung in the firmament, fierce and vivid, like a hunter’s moon. Invitations to him to return home and give a talk, a seminar, a lecture, anything he chose, flooded his mailbox. Caleb Hopsack congratulated his ‘star Twitter pupil’ and begged him to address the annual conference of the Ordinary People’s Party. It took a while for the phlegmatic citizens of Plasentza to grasp that the tweeter of the hour, a real-live Prince and property tycoon who’d broken the spell under which they’d been living for decades, was actually resident in the capital city of their country. But once his presence had been verified they were eager to hear him. They hadn’t realised how pusillanimous they were until, in 140 characters of fire, he’d shown them. They had practised tolerance for evildoers and tried to reintegrate them into society. They had cared for minorities and strangers, but now these same minorities appeared to them as self-pitying schismatics and those same strangers were planting bombs. What about their own needs? Who was speaking up for them?

Fracassus was.

Time to Muck Out the Pig-Pen, he tweeted, remembering a phrase his father had whispered into his crib.

Invited to discuss the Bomb as Opportunity at a meeting of the Plasentza Scientific and Philosophical Society, he drew huge crowds. He had feared he would have to make a speech of more than 140 characters and ordered Professor Probrius to write it for him, but the organisers assured him it would be enough if he simply mounted the rostrum and shouted ‘Kill the killer.’

‘Kill the killer,’ the crowd chanted back.

‘We’re too scarred,’ someone shouted. And then that too was picked up and passed from voice to voice.

Not knowing what to say, Fracassus turned his face sideways to the audience as he’d seen someone called Mussolini do in old newsreels. It was the very expression – though he could hardly be expected to remember that – with which he came into the world. He folded his arms and pursed his lips: a stance suggesting petulance on a Homeric scale. As though by divine chemistry, the audience was at once transformed into supplicants and Fracassus into a god who could stand there for eternity, waiting to be appeased. Nero, Mussolini, Fracassus.

‘Frac-Ass-Us!’ the people called.

Peevish and impassive, his fists clenched, Fracassus raised his chin and stared towards the east.

He left the stage still clenching his fists. Women fought to kiss his knuckles. ‘Such a boy,’ one said. ‘And yet such a man,’ said another.

‘You haven’t seen anything yet,’ he told them.

‘They haven’t heard anything yet either,’ Dr Cobalt muttered to Professor Probrius. They were standing to one side, waiting to escort him back to the hotel, not wanting to be seen. Fracassus was a prodigy. A monstrous and abnormal thing. He appeared from nowhere. It would disappoint the faithful to learn he had an elocution teacher and a life coach.

‘He has a terrific advantage,’ Probrius said, ‘in that they don’t actually come to hear him. There’s something about him that compels attention. It can’t be looks and it can’t be presence, because he has neither.’

‘Then what is it?’

‘I think it’s that very question. What is it? Why are we looking at him? He possesses the opposite to charisma to such a degree that people will stand for hours trying to figure out why they’re standing there for hours.’

‘But see how transfigured they look as they leave. It is as though they’ve been vouchsafed a vision.’

‘They have. A vision of themselves. He is a mirror into their secret selves. They applaud their own words and leave transported.’

‘He should go far.’

‘He will.’

But first he had to address the Plasentza Chamber of Commerce.

Observing his reluctance – for Fracassus had been asked not to make his ‘Kill the Killer’ speech in deference to the feelings of businessmen who might have thought he meant them, and he couldn’t remember what else he believed – Professor Probrius undertook to brief him, though his own understanding of business matters extended little beyond the conviction that the pursuit of money softened men’s brains.

‘Hardens them, you mean,’ Dr Cobalt said one night, by way of pillow talk.

‘I think that’s your politics talking,’ Probrius replied, supporting himself on one elbow. ‘In my experience, those we call businessmen are the quickest of any profession to be impressed by the platitudes of success; to be dazzled by the prosaic financial exploits of one another; and to invest the most basic tricks of their trade, though they don’t surpass the bartering of the schoolyard, with an unfathomable mystique. The whole science of business could be written on the back of a postcard.’

‘You’ve never heard of the rich crushing the poor?’

‘I have, my love. I have heard of it and observed it. But the cruellest of men can be gullible, and it is to tickle their gullibility that I am preparing the Prince.’

In which spirit he advised Fracassus …

To claim credit for what he hadn’t done. To inflate figures. To make much of little. To drop names of people he didn’t know. To invoke the sacred mysteries of the ‘deal’ and declare himself a master of its arts. To take delight in scoring the meanest of triumphs over the weakest of adversaries. To reverse the normal rules of polite society and brag about his worth. In short, to be himself.

How Fracassus beguiled an audience of bankers, fund-managers and developers three or four times his age, is the stuff of Plasentza business-com

munity legend. How he told them that he owned more properties than in actuality he did. How he omitted all mention of his father and presented himself as a phenomenon of self-generation. How he told them, above their gasps of admiration, that he aimed high. How he told them that he thought big. How he made the shape of something big with his hands. How he divided life into those who push and those who allow themselves to be pushed, and how he was a pusher. How he told them that the first law of business was to know what you wanted, and how he told them that the second law of business was to make sure that you got it. How he told them that enriching oneself was godly but enriching oneself at the expense of others was very heaven. How he told them that he paid no taxes, for to pay tax only showed one ran one’s business inefficiently. And therefore how he told them that he never would pay tax so long as there was a bone in his body …

As the audience of high-aimers and big thinkers rose to reward Fracassus with their admiration – for never had the things they thought found better expression – Professor Probrius counted himself satisfied.

‘Didn’t I tell you?’ he told Dr Cobalt.

‘To be proved right isn’t always to be vindicated morally,’ she said.

‘You mean what’s true shouldn’t be true.’

‘That’s exactly what I mean.’

Vindicated morally or not, Probrius had to admit himself surprised by how well Fracassus’s asseveration that he paid no tax was received, not only by the business leaders and captains of industry, but by the waiters and waitresses, the wine pourers, the glass polishers, the ushers, the security men, the sound engineers, and the members of the press. If the poorest of the poor had been here, Professor Probrius thought, they would have cheered with equal zest. Here, to all men, in an age of business, was the apotheosis of success: ONE WHO PAID NO TAX.

Yet again, Fracassus had his finger on the pulse.

Twitter, too, was busy that night.

Amazing guy. Remember to know what you want and get it. If only I’d known half of what he knows at his age. Amazing.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights