- Home

- Howard Jacobson

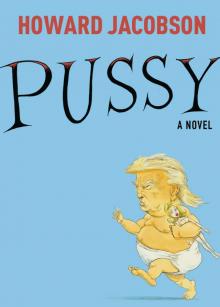

Pussy Page 9

Pussy Read online

Page 9

BOOK TWO

There is no such thing as the will of the people. There is only the will of those who tell the people what the people’s will should be.

Kolskeggur Probrius: Phonoethics: A Manual (Unpubl.)

CHAPTER 16

Containing the whole science of government

Great as was the consternation, and deep as was the sorrow in every heart, the moment for the Prince to leave came around without mishap or interference by the fates. Fracassus did nothing further untoward. And Sojjourner did not make a last-minute appearance. It was written. The world was waiting and it was time he ran into its embrace.

Professor Probrius and Dr Cobalt would accompany him, acting as mentors, confidants, travel guides and porters to the Prince and as eyes and ears to his parents. Report your every perturbation, they were told. But do not scruple to describe the highlights too.

Speaking for themselves, Professor Probrius and Dr Cobalt were delighted to be going. They too believed that indiscretions were best committed far from home.

The Grand Duke found it as hard as he knew it would be to bring the Grand Duchess round to Fracassus’s departure. He reminded her that they had often been away and left their son, but accepted that this was different. When they had gone travelling the boy was safely ensconced in the Palace with a television to watch in every room; now he would be wandering God knows where. Not without technology – to compensate for his cruel pulling of the plug, the Grand Duke lavished the latest phones and tablets and laptops on Fracassus; even a watch that would double as a direct video link to the Palace and fitness activity tracker – though you could never be sure how good the signals were going to be in foreign parts. But he had mature company. And there were signs that he was maturing himself, if one only knew where to look for them. He’d been seasoned by misfortune. He had taken up tweeting again and had more than a million avid followers.

The Grand Duke and Duchess decided against going to the heliport, fearing the parting would prove emotional They saw the party off at the Golden Gates. Renzo took his son in his arms and begged him in a voice thick with emotion to remember all the advice he’d given him over the years. He had a great future. All he had to do now was earn it. Look, listen, learn. Limp and unresponsive, Fracassus gave the impression of somebody who’d forgotten everything that had ever been said to him already. ‘Write to me,’ his mother said, catching Probrius and Cobalt exchanging ironic looks. ‘And I mean write, not tweet. I refuse to read those things.’

Wherever possible, Fracassus would travel first class, his tutors economy. This suited all parties. For their part, Professor Probrius and Dr Cobalt were pleased to have time together. They took that very particular pleasure in one another’s company reserved for people who look alike. Both had attenuated bodies and long necks, both were pared down into that leanness often found among servants of the wealthy, and both had complementary sideways tilts that came from having to whisper into each other’s ears in the presence of majesty. Thus they always looked hugger-mugger even when they weren’t. Just what their travelling relations would be had not yet been decided. They would leave it, they thought, as they had left it for the last few years, to chance and opportunity. They weren’t young and reckless like the Prince. They could wait. To tell the truth, they found postponement titillating.

Fracassus, who had yet to meet anyone his own age he resembled, had only himself for company. He didn’t mind that. He had always preferred his own presence to that of other people. Moving from television set to television set in the weeks his parents were away, he had been free to let his mind riot in future scenarios of power. Solitude, he discovered, particularly when passed in front of a television screen, could be phantasmagoric. There had been times when what was true and what was not were so hard to tell apart that Fracassus felt he was exercising power already. ‘Me,’ he would cry inwardly, and sometimes even outwardly, as Nero lowered his thumb and the bodies piled up in the Colosseum. ‘Me,’ he would proclaim – ‘Ich!’ – with every rewind of Max Schmeling flooring the Brown Bomber. Wrestlers, of course, were him. ‘Do you submit now?’ They didn’t just submit, they whimpered their surrender. And feral motorists. Leaping from the burning car and watching it explode on the outskirts of the Mexican village, he felt a passing twinge of something – pride, was it? – knowing the other passengers had not been so fleet of foot and quick of thought. ‘Me, me!’ Their own fault if they were burnt alive or scarred irremediably. A mariachi band played to show there were no hard feelings. The car had been worth half a million in whatever currency.

Well, ‘me’ was a trickier entity after meeting Sojjourner. Sojjourner, who’d loitered briefly in his thoughts like a scented candle (his own simile) and then went out. For that brief time ‘me’ had become ‘us’. But here he was, back to being singular again. He was surprised how quickly he’d got over the heartache and liked what it said about him. He was a tough guy. He was hurt-proof. Love is for pussies, he tweeted.

Though the helicopter flight to Gnossia was only half an hour – no more than a quick hop over the Wall – it irritated Fracassus that he had to travel the same class as everyone else. ‘Can I sit on my own if I buy the airline?’ he asked the pilot. ‘That’s not my decision, sir,’ the pilot told him. Retard, Fracassus thought.

A delegation of Gnossian Republicans greeted Fracassus and his party on their arrival. Though Gnossia and Urbs-Ludus were essentially the same country divided by a Wall, the air felt different to Fracassus. Professor Probrius pointed out that this was because there were fewer towers and ziggurats in Gnossia, so they could see the sky. Fracassus seemed disgusted by the idea of fewer towers and wondered why they’d come to such a hellhole. ‘Diplomacy, Your Highness,’ Probrius reminded him. ‘There has been tension between the two Republics. We are here to further your education, but let us not forget that this is, inter alia, a peace mission. The Grand Duke harbours high hopes for this visit. He believes you to have good negotiating skills.’

‘I have great negotiating skills.’

‘And that is why you’re here.’

‘Are these good hombres?’ he asked Probrius, sotto voce.

‘Very good.’

‘Then tell them we want peace. And tell them if they want a few more towers I’ll build them.’

‘It would sound weightier coming from you, Your Royal Highness.’

A small dinner of fish that Fracassus refused to eat was thrown in honour of the visiting party, after which the Prince was granted an audience – though he hadn’t asked for it – with the President of the Gnossian Republic, Eugenus Phonocrates. The President was elderly, and received Fracassus in his bed at the Presidential Palace. The President’s face was lined as though he had been sleeping on a crumpled pillow all his life. He was said to have kind eyes but Fracassus, who was said to have no eyes, couldn’t locate them in the great railway intersection of deep wrinkles.

‘I once met your father,’ Phonocrates said. ‘He must have told you that. It’s some years since we met but I see the family likeness in you.’

‘I have his hair,’ Fracassus said.

‘And I hope his good character.’

‘I have a great character,’ Fracassus said.

Phonocrates tried to sit up in bed and called Fracassus closer to him. It didn’t occur to Fracassus to offer help. ‘Many years ago,’ Phonocrates said, ‘your father told me he admired the way I ran my country and asked me to divulge to him the secret of good government. I told him that if he would ever do me the honour of sending his son to meet me, I would divulge it to him. You have an older brother, I believe. He never did come to see me. I don’t know why.’ (Transgender faggot, Fracassus decided against telling him.) ‘So I am doubly honoured that you have.’

Fracassus inclined his head. The President waited for him to say the honour was all his, but he didn’t say it.

‘Anyway,’ the President continued, ‘I am today pleased to be keeping my promise. That is not something I usua

lly do …’ He paused, coughed, and banged his chest. ‘And there you have it.’

Fracassus waited. ‘There I have what?’ he asked at last.

‘The whole secret of good government.’

‘Where? What?’

‘Don’t keep your promises.’

Fracassus had no idealism to be outraged, but even he was taken aback by the old man’s candour.

‘Not any?’

‘Not any … I know what you are thinking. I might have got away with not keeping some of my promises. But all! And maybe for a short time. But for more than sixty years! But this is to miss the point. And listen to me carefully now … To be successful in politics you must be thorough. If you are half-hearted you will fail. A half-hearted liar the people will not forgive. “Ah!” they will say, “did you hear that, did you notice that? He has just told a lie. He cannot be trusted.” But if they know you to be a liar through and through, and you show that you know they know you to be a liar, they can trust you. They grow fond of your lies. Eventually they will come to feel that the lies you tell are their lies. It is like pillow talk. Everyone lies in love. That’s the game. You don’t honestly believe what you say to one another. She is not really the most beautiful woman on the planet, and you are not really the most handsome man. But in the game of love you pretend it is so and think none the less of one another for telling lies and believing them. The game of politics is the same. Tomorrow you will all be employed – you promise. The day after tomorrow you will all have free healthcare. The day after that you will pay no taxes. Who really believes any of that is going to happen? Not the people, much as they would like to. And while they love me for telling them what they want to hear, they love me even more for the theatre of illusion I give them. They think I am the villain in a pantomime and everybody cheers the villain in a pantomime. You ask me are the people stupid. Very far from it. They can smell a fraud a thousand miles away. But ask me if they know what’s best for them, then the answer is a resounding no, because their besetting weakness is that they love a fraudster. If someone who wants the best for the people lets them down, they will never forgive him. But a joker who wants the worst for them they will follow into hell – this, Prince Fracassus, is what I would have told your father.’

The following morning, Eugenus Phonocrates, lover of the people, was found dead in his bed.

No one blamed Fracassus.

He stayed for the state funeral. Bells rang. Hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets. Men and women of all ages wept openly. Some cut their arms and faces. Any baby born that day, no matter what the sex, was named Eugenus Phonocrates.

At the biggest sporting arena a football match was called off so a memorial service could be held. Fracassus, as heir presumptive to the Duchy of Origen, was guest of honour. He sat between Phonocrates’ sons on a raised platform in the centre of the field, carried a candle, thought of Sojjourner in her trousers and wept a hard dry tear for the cameras.

Midway through the service, by which time the mourning had fed on itself like a flame, leaping from the mourners’ chests as though to be consumed by their own fervour was the only end they sought, a wild person wearing rags broke though the crowds and dropped at Fracassus’s feet. Carried away by the emotion sweeping through the stadium, the security services did nothing to remove the intruder. He was part of it. His own private conflagration.

Fracassus did what he always did when he was afraid and jutted his jaw.

‘Listen to them,’ the wild man said, as though to someone sitting on the Prince’s shoulder. ‘Behold the wondrousness of human folly.’

‘I don’t frighten easily,’ Fracassus said. ‘I have less fear than any man on the planet.’

The wild man ignored his words. ‘Look around you,’ he went on. ‘Man in his massed magnificence. Crowds screamed and cried for me once. Women said and did disgusting things. They encouraged their own daughters to do the same. They abandoned shame, if they had ever known it. I was the best-known singer in Gnossia. The Republic came to a halt when I sang. The radio fell silent. Doctors stopped performing operations. Tickets for my concerts changed hands for more than people paid for their houses. I loved the crazed attention. I studied every face. I drank in the adulation of every person in that crowd. I had the power not just to move but to possess. They weren’t listening to my voice, they were my voice. I loved it and then I hated it. I had thought it was about me but it wasn’t. It was about them. They screamed because they needed to scream. They waved their arms in the air like one great beast with a thousand limbs because they wanted to lose their humanity. That was the only way they could find themselves – by losing what made them separate. Singing, dancing, marching, sport, religion, mourning, war – they’re all the same when the great beast waves its million arms. Only by losing do they find. Something must have happened in the history of humanity that made people cast away their reason. Maybe it was the appearance of a strange planet. Maybe God descended. Maybe it was the applause humanity awarded itself when it moved in a mass out of the great soup of creation. “We’ve made it! We’ve done it! We’re here!” Whatever the cause, adulation for themselves in the appearance of another became a fixture of human life. You no doubt think that when you are applauded it’s because of something you have said, or done, or just because of the way you look. Disabuse yourself. You simply fill a vacuum. The need for you, whoever you are, was there long before you were. You are the object of the habit of hysteria, that’s all.’

Fracassus felt himself sliding into a trance. They can’t half talk, these Gnossians, he thought. Then, through half-closed eyes, he saw the once famous singer raise his hand. He’s going to kill me, Fracassus thought. It’s me he blames. He remembered Max Schmeling and made a fist. Then he landed it in the middle of the singer’s face.

Reports at once spread that as part of a well-orchestrated coup there’d been an attempt on the lives of Phonocrates’ grieving sons. Prince Fracassus, son of the Grand Duke of Origen, here from the Republic of Urbs-Ludus on a peace mission, had foiled it. Cheers mingled with tears. The habit of hysteria had gone looking for a cause and found it in Fracassus.

Back in the Palace of the Golden Gates, watching the late news on television, the Grand Duke saw it happen. He would have liked to call his wife but she was locked away in her fairy-grotto chocolate factory. ‘My boy!’ the Grand Duke said, alone.

Fracassus gave interviews to the world’s press gathered in Gnossia to report on Phonocrates’ funeral. The late President was a great guy, he said. He shook his head and, with a dying fall, repeated the felicitous phrase. ‘Great guy … great guy …’

Had he been frightened? No, he had no fear, no fear.

Anything else?

He raised his face to the cameras. ‘It’s been a great night, thank you, thank you.’ Then he remembered a line Professor Probrius had given him for a rainy day. ‘The fight against terror goes on.’

CHAPTER 17

A hero of our time

There being nothing further to keep them in Gnossia, the Prince’s party betook themselves to the little airport. Fracassus didn’t like flying but at least he had a row of first-class seats to himself. He settled in to watching television on the back of someone else’s seat in a tongue he didn’t recognise on a screen the size of a postage stamp.

Language had never been an insuperable barrier to Fracassus’s enjoyment of anything. The conversations he most enjoyed were the ones he couldn’t hear or understand and even his favourite television programmes worked best for him with the sound turned off so he could interpolate his own dialogue. Some people’s brains are crammed and noisy places; Fracassus – though he enjoyed commotion and liked imagining himself to be its cause – kept a quiet head. The word ‘me’ pinged about in it like a bagatelle ball in a deserted basilica.

And now ‘me’ was an entity they had tried to kill and failed. The word suggested impregnability. ‘Me’ was armour plating.

Soon after the plane took off,

he found himself engrossed in a game show, the essentials of which would have been plain in any tongue. Based loosely on a sketch by a once beloved foreign comedian called Monty Python – repeats of which Fracassus had watched a hundred times without finding them remotely funny, so there must have been nothing else on those nights – the show comprised a host wearing a faceted metallic suit, a hostess exiguously dressed in banknotes, a studio audience exceptionally collaborative in spirit, and the contestants themselves, tempted to blow the whistle on people they loved, whether by giving away their secrets to their spouses, divulging their medical histories, casting doubts on their legitimacy, or informing on them to the police. The longer they held out against betrayal, the plumper the brown paper envelope they were offered, though of course – or there would have been no point to the game – the offer might be rescinded at any time. You had to choose your moment. Those who refused to stab their friends in the back were jeered – ‘Spravnos,’ the studio audience called out, which Fracassus translated as ‘Lock ’em up!’ – while those who held out for more money and then sold their family down the river were applauded wildly. ‘Spravchik,’ the audience shouted, which Fracassus took to mean ‘We love you.’ Fracassus registered a provisional interest in the witch-queen hostess, part Lilith, part Shinigami, who handed out or held back the envelopes, dropping a curtsy either way, in order to avoid bending over. But it was the Tempter in Chief himself, brawny as a bear but soft-voiced like a serpent, who grabbed Fracassus’s attention. ‘Me,’ Fracassus thought, as the plane landed at Cholm airport.

A middlingly-stretch limousine was waiting to collect the party and transport them to their hotel. The cocktail cabinet and television were smaller than his father’s but Fracassus was, for him, too full of what he’d been watching on the flight to complain. ‘So what exactly was the principle of this game?’ Dr Cobalt asked. She would have liked to take in the scenery of a country she had never visited before, but this was not a journey for her pleasure. And besides, flushed from whatever had happened in Gnossia, Fracassus had turned voluble and peremptory.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights