- Home

- Howard Jacobson

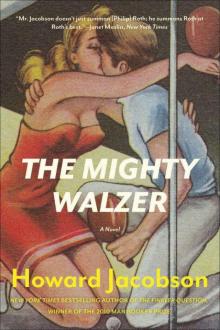

The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer Read online

Howard Jacobson

THE MIGHTY WALZER

A Novel

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

BOOK I

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

BOOK II

ONE

TWO

BOOK III

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

BOOK IV

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FINALE

ONE

Imprint

For the boys of the J. L. B.

and G. O. S. J. ping-pong teams,

remembering the glory days.

This mature novel has the sustained exuberance and passion of his youthful writing but within an epic ... an achingly funny book ... an amazing achievement ... There are few novelists today who can imbue the trifles of life with such poetry’

Independent

‘Jacobson writes with an agility that gives pleasure akin to humour even when it isn’t actually funny. It is the sheer charm of his intelligence that feels like wit. It is unlikely that anybody has ever written this well about table tennis before ... a superb piece of work, enormously enjoyable’

Sunday Times

‘A refreshing look back at Jacobson’s formative years, an era teeming with highly comical escapades and heart-breaking moments of solitude and pathos. The deeper insecuritites of a young man are brilliantly illuminated by Jacobson’s humour ... Raucous, funny and strongly recommended’

Time Out

‘A largely autobiographical rites of passage novel ... Much more than just a novel about the unlikely grace of a minor sport, this is Jacobson’s most tender and gentle comedy yet’

Express

‘Jacobson writes about ping-pong with fine, tender wit ... And genuinely funny, excoriating, warm and fantastical this book is too. At times, Jacobson’s writing reaches dizzy heights, fizzing and spinning like the balls Walzer hits’

Evening Standard

‘A very entertaining novel ... Jacobson has the gift of impeccable timing. This is a writer whose prose style is as close as possible to oral delivery and who yet maintains a standard of fluent precision impossible for any stand-up comedian ... remarkable’

Mail on Sunday

BOOK I

ONE

The racket may be of any size, shape or weight.

4.1 The Rules

SMALL BEGINNINGS. The principle of the oak tree, and the secret of the successful artist, politician, sportsman. Nice and easy does it. A box of Woolworths watercolours for your birthday, a volume of Churchill’s speeches, a cricket bat or a pair of boxing gloves in your Christmas stocking. And then the slow awakening of genius.

Softly, softly, catchee monkey.

No small beginnings or slow awakenings for me, though. My sporting life was shot through with grandiosity from day one.

Grandiosity was in the family. On my father’s side. Normally, when I speak of ‘the family’ I seem to mean my father’s side. Make what you like of that. My mother’s side went in for reserve. And that too was something my sporting life was shot through with from day one. Can you be simultaneously grandiose and reserved? Not without great cost to yourself, you can’t. But let’s stick to my father’s side to begin with, if only because my mother’s side wouldn’t want to be intruding itself on anyone’s notice so early in the piece.

And let’s pin it to a date. August 5, 1933. Dates are important in sport. They remind us that achievement is relative. One day someone will run a mile in zero time; thanks to improved diet and training methods they will cross the tape before they’ve left the blocks. But back in the fifties four minutes looked pretty fast. On August 5, 1933, the first ever World Yo-Yo Championships were held in the Higher Broughton Assembly Rooms, not far from where the River Irwell loops the loop at Kersal Dale, on the Manchester/Salford borders. From my grandparents’ chicken-coop house in Hightown my father could walk to the Higher Broughton Assembly Rooms in twenty minutes. That was on an ordinary day. On August 5, 1933, he walked it in zero time. Excitement. He was twelve years old. And carrying his Yo-Yo in a brown Rexine travelling-bag.

The Yo-Yo craze had swept the country the year before. Cometh the hour, cometh the toy. A Yo-Yo was the perfect Depression analgesic. Every unemployed person could afford to own one. It passed the time while you were hanging around on corners or standing in a bread queue. And it conveyed a powerful subliminal message — nothing stays down for ever. It’s even possible that in some sort of way Yo-Yos were seen as an antidote to Fascism. Not just because of the multiplicity of bright colours they came in but because they bred individualism, introversion even. A kid playing with his Yo-Yo was a kid not marching behind Oswald Mosley. This may have been one of the reasons the Yo-Yo craze lasted so much longer in Manchester, which was a Black Shirt stronghold, than anywhere else. Though for the most likely explanation of Manchester’s irresistible rise to Yo-Yo capital of the world you need look no further than the weaver’s shuttle. They’d been spinning cotton here for two hundred and fifty years; they’d been weavers of wool, slubbers of silk, distaffers of haberdashery, ribboners and elasticators, for centuries prior to that. Wristiness was in their blood the way grandiosity was in mine. Playing with a Yo-Yo was no more than they’d been trained to do since the Middle Ages.

In the face of an adeptness as ancient and inwrought as that, it was fantastical of my poor father to suppose he had a hope of impressing at the World Championships, let alone of lifting the title itself, on which he’d set his heart. He may have been Mancunian in the sense that he’d begun his life in a Manchester hospital bed — ‘It’s a lad!’ were the very first words he heard, ‘and a biggun’ too’ — but there had been no other Mancunian of any size in our family before him, and you can’t expect to barge into an alien culture and lift all it knows of touch and artistry in a single generation. Bug country, that was where we came from, the fields and marshes of the rock-choked River Bug, Letichev, Vinnitsa, Kamenets Podolski — around there. And all we’d been doing since the Middle Ages was growing beetroot and running away from Cossacks.

He couldn’t count on much support at the Assembly Rooms either. The only person he’d told that he was competing was his father. And he only told him on the morning of the competition.

I imagine my grandfather sitting in his rocking-chair, looking into space, listening to the ticking of a clock. Grandfather clock, you see. That’s how we make our associations. Though in fact he wasn’t anybody’s grandfather then. The rocking-chair won’t be accurate either — that too belongs to a later time. But I’d be right about him looking into space. The one thing he wouldn’t have been doing was reading. There were no books and no newspapers on my father’s side. I don’t mean few, I mean none. Although he owned reading-glasses towards the end of his life, and liked opening and closing them, I never once saw my father reading anything except the instructions that came with whatever new shmondrie he was playing with and the notes my mother wrote (in capital letters and on lined paper) to help him with his patter when he was standing on the back of his lorry pitching out chalk ornaments on Oswestry market. He was so unfamiliar with books that when I presented him with mine (mine, ha! — some book, forty pages of black and white diagrams and dotted lines, illustrating the hows of the high-toss service and the topspin lob), he marvelled that I’d gone to the expense of having a special copy printed with the dedication for my father, Joel Walzer, who taught me to aim high. ‘Dad, it’s not a special copy,’ I had to explain

to him, ‘they’re all dedicated to you. It’s called a print run.’

‘All of them? Sheesh! That’s very nice of you, Oliver.’

After that he took it everywhere with him — he would have taken the whole print run everywhere with him had it been practical — even to bed, my mother told me, where he’d sit up and stare at it for hours on end. ‘I think I’m beginning to get the hang of this,’ he told her one night. I asked her if she knew how far he’d got. Yes, she did as a matter of fact. He’d got to the bottom of the page opposite the dedication to him, where it says ‘This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, no part may be reproduced … without the prior permission of the publisher.’

But then who has time for books when they’ve a living to earn? And when their head’s full of big plans.

And big disappointments.

What my grandfather actually said on the morning I imagine him looking bookless into space I know from my father. He said, ‘Keep your voice down.’

‘It’s all right, she’s upstairs.’

‘And stairs don’t have ears? Use your loaf. Do you want to kill her?’

He did quite want to kill her, yes. They both did. But the real issue was did he want her to kill him. ‘No,’ he said.

‘Then hob saichel! Keep your voice down. What time are you on?’

My father wasn’t sure what time he was on. Only that he was contestant No. 180.

‘My advice to you,’ my grandfather whispered to him, looking anxiously at the ceiling, above which prowled the snorting beast, my grandmother, ‘is not to watch the previous one hundred and seventy-nine. Go somewhere quiet. See if you can find a dark place to sit, or better still lie down. And don’t show your face till they call your number. Now geh gesunterhait. If I can get away to come and watch you, I will. But if I can’t, have mazel.’

He knew about nerves, my grandfather. Not as much as my mother’s side knew about nerves, but he knew specifically about stage nerves, which they didn’t. He had once auditioned to be a Midget Minstrel for the Children’s Black and White Christy Minstrel Troupe. It’s been said of all the men in my family - father’s side, father’s side — that we are built like brick shithouses. The shit part I take to be gratuitous; the house, however, gets something about our rectilineal outline. Even as a boy my grandfather was well on the way to being that hugely comical hexahedral shape, like a walking sugar cube (except, of course, that as a Christy Minstrel he was expected to be black), which he subsequently bequeathed to my father and indeed to me. That was what failed him his audition. You can’t be a Midget Minstrel at five feet nine and three-quarter inches in all directions. He could have made it as a lyric tenor maybe, but for my grandfather these were the Jolson not the Caruso years. What he wanted was to jerk around, to be loose-limbed, not to stand like a shlump in a monkey-suit and hit high notes. He liked blacking-up, rolling his eyes, playing the banjo, telling Mr Interlocutor jokes and tap-dancing. Photographs still in my possession suggest that his glove work must have been excellent and that he could have out-horripilated anyone in the business. No small mastery of Western ways for someone who had been carried all the way from Zvenigorodka tied in a shawl like a leaking picnic lunch only a dozen years before.

No doubt, as he put his arms around my father and wished him mazel, he was remembering the day mazel had deserted him. ‘You’re too big, son,’ they’d told him. ‘You’ve got a kid’s voice in a man’s body. Come back and try the seniors when you’ve got a voice that goes with your build.’ But who could afford to hang around in those days? Many years later, when it no longer mattered, he was able to make light of it. ‘You don’t understand, Charlie. I coulda had class. I coulda been a shvartzer.’ But in 1933 he was less philosophical. In 1933 he was a machinist with a bad back and olive hollows round his eyes, grafting in a poorly lit raincoat factory in Strangeways, next door to the prison. (‘Me and God together — He works in strange ways, and so do I.’) His head wasn’t filled with darky melodies any more, only the sound of sirens. Sometimes he would switch off his machine, thinking that the siren he heard was signalling knocking-off time, whereas it was still only four o’clock — pitch-black outside but still only four o’clock — and the siren was coming from the prison, warning of a break-out.

He womanized. What was he supposed to do, sweating in the shadow of a phallic prison six days a week? He was built like a prison himself — a brick shithouse — entertained grandiose illusions, wore a wicked Rupert of Hentzau moustache, was full of juice and jokes, and loved to look down and see appreciation swimming in the eyes of another man’s unclothed wife — what else was he ever going to do with his life except womanize it away?

And since he womanized, my grandmother tyrannized. Isn’t that how it goes?

He chases skirt, so she gives what for.

Her giving what for embraced her children as well as her husband. Whether it extended to her grandchildren too I can’t remember. I was scared of her, I know that. But that was mainly because she was swarthy and reminded me of a gypsy. Of all of us she was the only one who looked as though she still had mud from the Bug and the Dniester on her. And some of the old religion mixed in with it. Every Passover and Yom Kippur, according to my father, she’d box the family’s ears. Every Succoth and Shevuoth the same. Every Chanukkah and Purim. Good yomtov, klop! ‘But at least that way,’ he said, ‘we got to know the festivals.’

This was why there was so much whispering afoot on the morning my father confided to his father his intention of competing in the World Yo-Yo Championships — August 5, 1933, was a Saturday, and Saturday, by my grandmother’s reckoning, was meant to be a day of rest from everything except her.

It’s my understanding of the thirties that when it came to observance we Walzers were essentially no different from most other families who’d made it over from some sucking bog outside Proskurov the generation before. We’d done it, that’s where we stood on the question. We’d done observant, now we were ready to do forgetful. If a Cohen wanted to change his name to Cornwallis, that was his affair. It was no mystery to any of us how come Hyman Kravtchik could go to bed one night as himself and the next morning wake as Henry Kay De Ville Chadwick. Enough with the ringlets and the fringes. Enough with the medieval magic. But we still bris’d and barmitzvah’d — klop! — and the seventh day was still the seventh day. Nothing fanatical; no sitting nodding in the dark or denying yourself hot food; no imaginary pieces of string beyond which you didn’t dare push the pram; and if you had to travel to see someone sick, you travelled — and you bought them fruit. All else being equal, though — which was where my grandmother put her foot down and k’vitshed and klogged and cried veh iz mir! and tore her hair and clutched her heart and tore everyone else’s hair — you rested. And even my father could see that competing in the World Yo-Yo Championships on a Shabbes wasn’t resting.

But that was not the reason, not the primary reason he slipped out of the house with his Yo-Yo concealed inside a holdall. Naturally, unless he meant for his mother to burst a couple of blood vessels — his, not hers — he wouldn’t have wanted her to see what he was carrying. But he didn’t want anyone to see what he was carrying. His Yo-Yo was a secret weapon which no one at all knew about and which he would unveil for the first time only at the World Championships themselves. It might cross your mind, in that case, to wonder whether his trouser pocket wouldn’t have served just as well as a hiding place, better even in that it wouldn’t have attracted anything like so much notice. Have I not said that my father was grandiose? The truth is, the Yo-Yo with which he was planning to storm the World Championships, the Yo-Yo he had not simply gone out and bought from a toy shop like every other competitor but had spent weeks constructing, taking sheets of plywood and a fretsaw and a pot of glue to bed with him, working at night under his blankets so that not even his brothers should know what he was about, was on a scale utterly disproportionate to anything we normally

associate with the contents of a boy’s trouser pocket.

This was why he was so confident. He had read and re-read the rules of the competition. (The last big piece of reading he ever did.) Nowhere did it say that a Yo-Yo had to approximate to the size of a cricket ball. Nowhere did it say that you couldn’t walk the dog with a Yo-Yo as big as a bicycle wheel.

When my father died, almost sixty years to the day after he’d competed in the first ever World Yo-Yo Championships, and in a house still not much more than a twenty-minute walk from where the River Irwell tries to hang itself on Kersal Dale — people I didn’t recognize stopped me in the street to tell me how much they’d loved him. ‘He had a big heart, your father,’ they all wanted me to know. They looked at me in a peculiar and personal way when they said this, as though his big-heartedness might have been lost on me, not a virtue I valued, or as though it was the one thing I hadn’t inherited from him. Grandiosity yes, big-heartedness no.

One of his old friends, Merton Bobker, to whom my father had lent money before Merton won the pools and was in a position to pay the loan back (which he didn’t do), actually held me by the sleeve and wouldn’t release me until I gave him tangible proof I’d grasped the difference. ‘There are plenty of big dealers around,’ he said. He was dripping at the eyes and mouth, like an abandoned labrador. ‘You understand? In this town big dealers come cheap. But your father was a big man. Get me?’

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

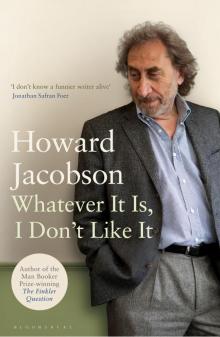

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

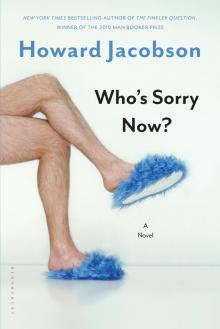

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights