- Home

- Howard Jacobson

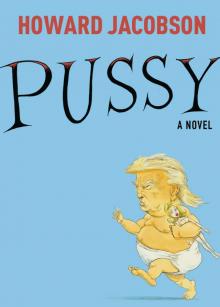

Pussy

Pussy Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Also by Howard Jacobson

Dedication

Title Page

Epigraph

Book One

Revelation

Prologue: The March of Ignorance

Chapter 1: In which Fracassus, heir presumptive to the Duchy of Origen, is born

Chapter 2: Concerning a father’s fears and a tutor’s skirt

Chapter 3: In which language is discerned to go backwards

Chapter 4: Concerning the part played by television in the education of a leader

Chapter 5: A painful chapter containing matters it were better to remain silent about

Chapter 6: In which it is agreed not to scare the horses

Chapter 7: A wind blows through the Republic of Urbs-Ludus

Chapter 8: The end of stupidity

Chapter 9: In which Fracassus is taught an important lesson about tax avoidance and has a bright idea

Chapter 10: How a weatherman brought sunshine into the Prince’s heart

Chapter 11: A short chapter concerning bricks and mortar

Chapter 12: A mother worries in 140 characters

Chapter 13: In which Fracassus informs the world what he’s eating

Chapter 14: When my love swears that she is made of truth …

Chapter 15: … I do believe her though I know she lies

Book Two

Chapter 16: Containing the whole science of government

Chapter 17: A hero of our time

Chapter 18: In which Fracassus almost reads a book

Chapter 19: The spirit of the jungle

Chapter 20: Fracassus discovers the price of freedom and tweets about it

Chapter 21: The loneliness of the braggart

Chapter 22: In which the Prince forms an even higher estimate of his gifts

Chapter 23: A short chapter with no lessons to be learnt therefrom

Chapter 24: On the sadness of things. A son returns, a father prepares to depart

Chapter 25: ‘Stop it!’

Chapter 26: Retards

Chapter 27: In which Fracassus proves he is no longer in love

Chapter 28: A brief treatise on buffoonery

Chapter 29: The speed of lies

Chapter 30: The end of days

Copyright

About the Book

Pussy is the story of Prince Fracassus, heir presumptive to the Duchy of Origen, famed for its golden-gated skyscrapers and casinos, who passes his boyhood watching reality shows on TV, imagining himself to be the Roman Emperor Nero, and fantasizing about hookers. He is idle, boastful, thin-skinned and egotistic; has no manners, no curiosity, no knowledge, no idea and no words in which to express them. Could he, in that case, be the very leader to make the country great again?

About the Author

Howard Jacobson has written fifteen novels and five works of non-fiction. He won the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Award in 2000 for The Mighty Walzer and then again in 2013 for Zoo Time. In 2010 he won the Man Booker Prize for The Finkler Question and was also shortlisted for the prize in 2014 for his most recent novel, J.

ALSO BY HOWARD JACOBSON

FICTION

Coming From Behind

Peeping Tom

Redback

The Very Model of a Man

No More Mr Nice Guy

The Mighty Walzer

Who’s Sorry Now

The Making of Henry

Kalooki Nights

The Act of Love

The Finkler Question

Zoo Time

J: A Novel

Shylock is My Name

NON-FICTION

Shakespeare’s Magnanimity (with Wilbur Sanders)

In the Land of Oz

Roots Schmoots

Seriously Funny: An Argument for Comedy

Whatever It Is, I Don’t Like It

The Dog’s Last Walk

The Swag Man (Kindle Single)

When Will Jews Be Forgiven The Holocaust? (Kindle Single)

To Donald Zec – the best of talkers, the best of listeners, the best of friends

HOWARD JACOBSON

PUSSY

with illustrations by

CHRIS RIDDELL

How is it possible to expect that Mankind will take

Advice, when they will not so much as take Warning?

Jonathan Swift

BOOK ONE

REVELATION

And I stood upon the sand of the sea, and saw a beast rise up out of the sea …

And the beast which I saw was like unto a hyena; and his feet were as the feet of a clown; and his face was as the face of a spoiled child …

And the people gave him his power, and his seat, and great authority …

And they worshipped the beast, saying: Who is like unto the beast? who is able to make war with him?

And there was given unto him a mouth speaking foolish things …

And he opened his mouth in blasphemy against truth …

And it shall come to pass that all who dwell upon the earth shall wonder that they worshipped him …

And they shall know that the beast came not out of the sea but their own hearts …

And they shall fear that once let out, the beast will never be persuaded to go back in again.

PROLOGUE

The March of Ignorance

Early one morning in the famously hot winter of 20** a figure could be seen walking between the tallest obelisks and ziggurats of the walled Republic of Urbs-Ludus. He was looking for the Palace of the Golden Gates and was assured he would not miss it. He was a lean man in his middle forties, of more than average height but lacking hair. Though most of the people he passed pretended not to feel the heat and remained buttoned-up and scarfed, he carried his overcoat over his shoulder. Something about him – it could have been his shaved head, for this was a society that set great store by fantastical coiffure – suggested intransigence and maybe even a fall from authority. He was Professor Kolskeggur Probrius and had, until the year previously, been head of Phonoethics, a university research programme looking into the importance of language to ethical thinking. The words we used and the way we expressed them, he argued, affected the thoughts we had and the actions we took. ‘Bad grammar leads to bad men’ hardly does justice to the subtlety of his thinking, but that was the gist of it.

A bachelor of austere habits, he had earned the esteem of students on account of his dedication to their improvement. Then came the Great Purge of the Illuminati, and Professor Probrius found himself accused of cognitive condescension, that is to say of making a virtue of possessing expert knowledge. Students were distressed by the perceived distance between his attainments and their own. They were made to feel inferior to him and looked down upon. It was conceded that he made efforts to lead students out of perplexity by finding other words for those they found distressing, but that had only resulted, they submitted, in making them feel remedialised. The moment he claimed ignorance of the verb ‘to remedialise’ was the moment that sealed his fate. There it was: he believed language belonged to him. At a specially convened hearing of the Thumb Court seventy-seven thumbs went down while only two went up. Thumb Culture made no provision for abstention. Professor Probrius was out of a job.

It was as the instructions had promised. He could not miss the Palace of the Golden Gates. It was taller by at least a dozen storeys than all the other ziggurats, it bore the name ORIGEN in large letters above the entrance and then again at sky level, and it had golden gates.

Buses were already congregating in the concourse outside the Palace, spilling lucre-tourists who marked it in their I-Spy Book of Monoliths before being driven off to the next

one.

A protest was taking place in what appeared to be a designated protest pen. From the spirit in which the demonstration was being policed, Professor Probrius deduced it was a regular occurrence and posed no immediate threat to the building’s security. As the symbolic focus of the Republic’s satisfaction in itself, the Palace had been the scene, three years previously, of the first of the Artisanal Bread Riots, the most violent public disturbance in the Republic’s history. For years, the only activity in Urbs-Ludus had been the construction of towers. Nothing else was made. Even the bread was flown in from somewhere else and invariably arrived stale. Sick of white sliced loaves, dry muffins and inelastic pizza bases, the populace demonstrated in such numbers that the authorities had to import a labour force of skilled dough-makers from countries outside the Wall. But there was an unexpected consequence. Soon, Urbs-Ludus woke to the realisation that the Republic was flooded – not with artisanal bread but with artisans.

One section of the population turned against the other. The wealthy had their brioches but the poor had to queue in hospitals behind those who made them. Crime increased – petty larcenies at first, but then offences against the person, especially against women whom, it appeared, many artisans had never previously encountered, at least not in the immodest dress considered appropriate, in the Republic, for the wives and daughters of property developers. Viewed within the Palace as further proof of man’s insatiable ingratitude, this latest disgruntlement was permitted to express itself, quietly, where it could be monitored. But there could be no doubt that the populace – albeit a different social stratum thereof – was on the growl again.

Professor Probrius had come to the Palace to be interviewed for the position of tutor to the Grand Duke of Origen’s second son – but now, due to unforeseen circumstances, the heir presumptive – Fracassus. He introduced himself at reception, where they looked so affronted to see him not wearing a coat that he thought it wiser to put it on before taking it off. Security was strict but smiling. He was required to show three forms of identification and leave his smartphone in a pigeonhole marked ‘Information Transmission Devices’. Two security officers patted him down, one for one leg, one for the other. A third, wearing a face mask, asked him to say ‘Ah!’ into a balloon. There was no knowing what means the latest enemies of the Game Economy, whether artisanophiles or artisanophobes, would deploy next, and germ warfare, passed from mouth to mouth, could not be ruled out. Professor Probrius exhaled. ‘Ah!’ The balloon filled but didn’t change colour. No one seemed to have expected it would. Then he was invited to take a seat. Above the reception desk was a painting in the style of Titian showing the Grand Duke playing golf with the Pope. Professor Probrius shook his head as though it were a kaleidoscope and he wanted to change the shapes in it. There was so much light reflected from the crystal chandeliers that it was possible he was not seeing what was really there. But no: there, leaning on his silver putter, was the Grand Duke of Origen, and opposite him, and laughing, with a cardinal standing in as his caddy, was the Pope. The only remaining question was whether the painting commemorated a real event or a fantasy one.

Eventually he was shown up in a lift to the 117th floor and ushered into the presence of the Grand Duke and Duchess. Though they’d been sitting at a table playing the board game Cashflow, which the Grand Duchess, wanting a quiet life, always allowed the Grand Duke to win, they were dressed and primped as though in expectation of a film crew, the Grand Duke powdered and wearing his medals, the Grand Duchess, more powdered still, in a vertiginously low-cut sequinned evening gown that appeared to be entirely open, but for a paper clip, on one side. She must have had her perilously high high-heel shoes off because she was still sliding into them as he arrived. Professor Probrius, not wanting to stare at her feet, counted her ribs. She was taller than the Grand Duke by a head and Probrius thought, from the appreciative glances the Grand Duke from time to time threw up at her, that he liked this and wouldn’t at all have minded had she been taller by two heads. Both had hair the colour of lemon custard, the Grand Duchess’s long and irritably girlish like Alice in Wonderland’s, the Grand Duke’s layered as though to resemble the millefeuilles now on sale in good patisseries throughout the Republic. Professor Probrius couldn’t tell how old they were. The expression ‘eternally youthful’ popped into his head. The Grand Duchess had had the usual surgery done on her breasts and looked wearied with all she had to carry.

Professor Probrius was greeted familiarly, the Grand Duke clapping him on the shoulder as Probrius imagined him clapping the Pope on the eighteenth tee.

‘Bitterly cold outside today, I hear,’ the Grand Duke said.

Probrius wasn’t sure how to reply. He was a man of principles, but one of those principles was not to make an unnecessary enemy of the powerful.

‘I haven’t found it so, Your Highness,’ he replied. ‘But then it’s possible I carry my own eco-climate around with me.’

‘You are a lucky man, Professor,’ the Grand Duke said. ‘We have nuclear heating in the Palace, but we still freeze. I have put out an order for all our staff to wear an extra cardigan today.’

Such is the power of suggestion that Professor Probrius fretted briefly for the Grand Duchess, who would have been exposed to the cold had it not been hot.

She smiled, noting his concern and pulled her gown together.

‘The Grand Duchess, too,’ the Grand Duke said, ‘must carry her own eco-climate around with her. She won’t hear of throwing on a cardigan.’

Professor Probrius wasn’t sure if a compliment to the Grand Duchess’s hardiness was called for. Fortunately, she came to his assistance before he could frame one. ‘It would be nice, Professor,’ she said, inching forward, ‘if we had a photograph. We photograph all our guests.’

Professor Probrius assumed this was a euphemism for another security check and readied himself for saying ‘Ah!’ again, but the royal couple simply positioned themselves on either side of him. The Grand Duchess fished about in her reticule, found what she was looking for and shot out an arm. Were arms answering the law of dynamic evolutionary process and getting longer, Probrius just had time to wonder before the Grand Duchess said ‘Smile.’ Then, laughing, she took a selfie.

Above them, on a bank of monitors, the Grand Duchess could be seen taking a selfie of herself taking a selfie in triplicate.

Walking with a slight skipping movement reminiscent of a girl on a hopscotch rug, she led the way into an adjoining room where a grand tea table was set as though for a delegation of a thousand. A ten-tier porcelain tea stand replicating an Origen tower spilled children’s party food – cupcakes in pastel colours, mini hot dogs, bagel snakes and potato men with Smarties for eyes. Probrius was offered a milkshake and invited to pick his own colour straw.

Through the heat haze, the room offered magnificent views of the city. ‘It’s from this window,’ the Grand Duchess said, ‘that we look down on our competitors.’

‘My wife, Professor,’ the Grand Duke said, ‘has a colourful turn of expression. It comes from being born in another country and reading books. Competitors is not how I think of them.’

There followed a complicated description, with which even Professor Probrius found it difficult to keep pace, of the meritocratic system that awarded titles to developers in proportion to the height and luxury-quotient of the hotel complexes, apartment blocks, shopping malls and the like which they had erected. Thus, while a couple of condominiums and an out-of-town gaming resort might get you a baronetcy, it wouldn’t make you a viscount. Things had come a long way, he reminded the Professor, from the Monopoly they had all played as children, where a modest bungalow on your property could bankrupt your opponent. The Grand Duke himself was in the fantasy market today, and kept his title on the understanding that he’d go on dazzling the discontented with bright lights, inner-city ski-runs and infinity pools. It mattered not a jot that they could never afford to stay in one of his fortified hotels. It was enough that they knew of th

eir existence. To his son Fracassus would fall the burden of extending the scale of irresponsible development – irresponsible in the sense of unconfined – set by the House of Origen.

‘He means increasing the profits,’ the Grand Duchess put in.

She pronounced the word with such a proliferation of fffs that Professor Probrius wondered if it had another meaning in her native country. He also wondered whether, at some level in their marriage, the Grand Duke and Duchess were at war.

‘My wife,’ the Grand Duke continued, ‘is a mother. She worries about the pressure on her son. The higher Fracassus climbs, in her eyes, the further he has to fall. But men only fall because they lose their concentration, spread their interests, notice other things; Fracassus has no interests and notices nothing. When we play Monopoly he throws the dice as though they’re hand grenades. He builds a city while I’m languishing in jail. Forgive me if I take pride in him. He isn’t as other boys are. He doesn’t waste time collecting stamps, listening to music or telling jokes. It’s to his credit that he doesn’t get a joke. Fun for Fracassus is victory. Play for Fracassus is war.’

The Grand Duchess stole a glance at Professor Probrius, as though to forge an early alliance of the sensitive.

‘So,’ the Grand Duke pronounced, once tea was cleared away. ‘Shall we get down to business?’

‘Certainly,’ said Professor Probrius, finding his most charming smile and thinking how wonderful it was no longer to be in a university environment and having to watch every word he uttered. ‘À nos moutons.’

The Grand Duke looked to the Grand Duchess and the Grand Duchess looked to the Grand Duke. It was as though, whatever the nature of their struggle, they were as one again and had unanimously decided, that very minute, that they had found the right man.

‘Let’s be on first-name terms,’ the Grand Duchess said.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights