- Home

- Howard Jacobson

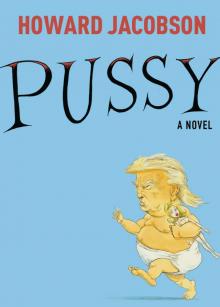

Pussy Page 2

Pussy Read online

Page 2

Probrius inclined his head. ‘I’m Kolskeggur, Your Highnesses,’ he said.

‘And we are the Grand Duke and Duchess of Origen,’ the Grand Duke replied. ‘Now here’s our little problem …’

CHAPTER 1

In which Fracassus, heir presumptive to the Duchy of Origen, is born

As the birth of potentates in the walled Republic of Urbs-Ludus went, the birth of Prince Fracassus was not especially auspicious. No thunderbolt struck the Palace. A star never before seen did not appear brighter than a meteor in the morning sky. Lionesses did not whelp in the streets. If anything, it was a quiet day. The Grand Duke arrived home earlier than usual from golf. It was not the Grand Duchess’s first lying-in, so – although they say the pain of childbirth is soon forgotten – she knew what to expect. She screamed only once, causing the Grand Duke to set down the comic pages of his newspaper and carefully run his fingers around his hair. Anxiety flattened it. ‘Make sure she has all the books she needs,’ he phoned through to the midwife. Then he rang his stockbroker-in-chief. ‘It’s about to happen,’ he said. ‘Buy. Unless you think we should sell.’

He waited for a telegram from the Prime Mover of All the Republics but none came. He shouldn’t have been surprised. Executive power in the Federation of All the Republics was vested in commoners who looked down their noses at the petty titled meritocrats who ran their individual Republics like medieval fiefdoms. At the same time they chafed against the popularity which these Grand Dukes and Duchesses enjoyed by virtue of their showy wealth. The people gloried in their titles. Gasped at their cloud-capped towers. Gaped at their gold. What did the Prime Mover and his bureaucrats have to rival this? They passed unpopular laws and skulked in low-rise offices on an apron of mulchy marshland which the Monopoly aristocrats called the Pig-Pen and wouldn’t have bought had their dice landed on it every time they threw. The Pig-Pen, as a matter of interest, was also the name the Executive gave to the concentrations of towers and ziggurats where the Grand Dukes and Duchesses conducted their business lives. Each party, when it inveighed against the ineffectiveness and corruption of the other, spoke of Mucking Out the Pig-Pen.

There was, in short, no love lost between the Federation’s competing oligarchies, and so no telegram congratulating the Grand Duke on the birth of a second son on whom the future continuation of his dynasty depended, was sent.

The Grand Duke was asleep when Prince Fracassus was born.

There was a reason for this lukewarmness. Fracassus had an older brother. Jago. Of Jago everything had been expected but none of it delivered. Once bitten, the Grand Duke contained himself. He was not a bitter man. The Republic of Urbs-Ludus, as overseen by the House of Origen, promoted petty grievances not grand resentments and as Grand Duke he had to be forever setting an example. He would not rail against enemies or fate. And he would not again tempt either by showing the size of his expectations.

Thus neither longed for nor dreaded, but no sooner incarnated than hosanna’d – for he was, for all to see, an Origen, with the tiny eyes indicative of petty grievance, the pout of pettishness, and a head of hair already the colour of the Palace gates – Fracassus came griping into the world in expectation of every blessing that a fond father, a copper-bottomed construction empire, a fiscal system sympathetic to the principle of play, and an age grown weary of making informed judgements could lavish, short, that is, of a sweet nature, a generous disposition, an ability to accept criticism, a sense of the ridiculous, quick apprehension, and a way with words.

Of these deficiencies Fracassus lived the early part of his life in blissful ignorance. How different was he, really, from the usual run of children? No baby is magnanimous; all infants have thin skin; small boys will often mistake boisterousness for mirth and bullying for wit; and wordlessness, as is well known, is something children grow out of at different rates. Many a great orator begins life as a tongue-tied toddler, indeed the greatest orators in Urbs-Ludus’s history remained that way.

So Fracassus’s parents had no reason to notice anything amiss and they too lived in blissful ignorance of his shortcomings, if shortcomings they could be called. He was an ordinarily pugnacious, self-involved and boastful child, not much attentive to the world around him and used to getting his own way.

Visitors to the Palace did what visitors to palaces do and doted on the heir presumptive. That he took not the slightest notice of any of them was evidence both of his self-sufficiency and the richness of his interior life. That he cried the moment he was denied whatever it was his little fingers reached for only proved his resolution. That he never spoke a word they recognised suggested he was already master of innumerable foreign languages. That he spat and spewed and farted in their company only showed his indifference to the world’s opinion.

It hardly needs saying that in a republic whose power resided in the spell of awe and majesty it wove around its citizens, the Internet enjoyed high esteem. The Great Duke lent his name to a dozen blogs and funded any website that promoted values close to his heart – the freedom to drink sugary drinks, to choose an example at random. Of these, the foremost at the time of the Grand Duchess’s lying-in was Brightstar, a platform for nativist, homophobic, conspirationist, anti-mongrelist ethno-nationalism which might have caused greater concern to people in high places had they only known what any of those words meant.

Brightstar saw the advantage in associating itself with Prince Fracassus from the moment of his birth. Indeed, it charted his development with such sycophancy that some subscribers to the site weren’t entirely sure whether they were a reading a paean to the Prince or a parody of him. Was there a difference, anyway? However to understand it, the Prince’s extraordinary untutored mastery of foreign tongues was painstakingly explored. Noises he had made were phonetically laid out and readers were invited either to guess at their meanings or confirm, should they be speakers of those hypothesised languages themselves, their lingual accuracy. At this early age, Fracassus was already becoming an inspiration, an example to the people of what freedom from instruction could achieve.

In one of those brief political reversals to which any truly original site is subject, Brightstar was compelled to cease publishing for a while and some of its pages were lost beyond recovery. So there is no way to confirm that on the Prince’s second birthday his water was bottled and, for a nominal sum, offered to subscribers, together with a certificate of authentication in his own hand. Porcelain pillboxes containing samples of his ordure the same. Some say this is malicious fabrication but there are people who claim to have purchased one or other or both and to have them still.

Among the Grand Duke’s and Duchess’s closest friends the usual jealousies stood in the way of adulation on quite that scale. A little more animation wouldn’t have gone amiss, they muttered among themselves. A prince wasn’t expected to show intellectual promise, but wasn’t this Prince slow beyond the usual meaning of the word? And those eyes – were they ever going to open? But out loud they voiced only praise. ‘He will be an ornament to your Dynasty. He will be a flower in the garden of the Republic. He will be a prince among princes.’ The Grand Duke liked the idea of his son as ‘ornament’, wasn’t sure about ‘flower’, but took strong objection to that equalising ‘among’. His son, he hoped, would leave the others in his wake. The rest were not princes but ten-a-penny princelings, as ineffective as that ancien régime from whom, along with weak chins and syphilis, they’d borrowed their titles. Some couldn’t even afford to live in their own tower blocks.

Concealed in his contempt for minor Monopoly aristocrats was a gnawing consciousness of inferiority that could only be explained as shame at being a Monopoly aristocrat himself. The Grand Duke looked down on everybody except those who looked down on him – the gubernatorial classes, unpropertied, untitled, unnoticed by the media and often badly dressed, but wise in the ways of governance and exercising an influence which couldn’t be quantified but for that very reason attracted a near mystical envy and respect. For all

his wealth and eminence, the Grand Duke had never met the Prime Mover of All the Republics, whose pronouncements, though delivered from an undistinguished address, were listened to the world over.

The Grand Duke was stung.

Secretly, his ambitions for his son were unbounded. The name of Origen could climb higher yet into the empyrean. Fracassus would build betting halls of such magnificence that only gods could afford to play in them. But after that … after that the Grand Duke looked to his son to Muck Out the Pig-Pen, seize the levers of power, and win for the House of Origen the mystical respect which had so far eluded it.

And then they’d see who’d spurn the advances of whom.

The Grand Duke did not lack realism. His was a republic within a republic, admired and emulated, yet for all its devotion to innocent indulgence, it had always had its critics – mumblers and fly-posters, half-day insurrectionists who sat down on rubber yoga mats and read their messages. There was no violence; it was hard to be angry outside the Palace of the Golden Gates. The building made people smile. They enjoyed looking up and feeling dizzy. Even the homeless liked to see where other people lived. But recently, encouraged by the success of the Artisanal Bread Riots, these demonstrations had got more boisterous. The Grand Duke was a lover of social platforms, but these too spread disaffection, stoking envy and encouraging the unhappy to pick publicly at one another’s scabs. Follow-my-leader discontent, he called it.

In one chill corner of the Grand Duke’s mind crouched calamity. The ladder was tall and the snake was slippery. You couldn’t count on staying at the top. But by the same logic, nor could the Prime Mover. Thus was the Grand Duke able to see, in the very thing he feared, the very thing he craved: the Pigs cleared out of the Pig-Pen and Fracassus atop the world.

Behind their hands, people close to the Palace said the Grand Duke’s natural optimism blinded him to the truth about his son’s character and abilities. Others thought he had shrewdly read the age and knew precisely what it demanded: the last person for the job could easily turn out to be the first person for the job.

The Grand Duchess was too wound around in sorrow to have a view about the infant Fracassus either way. She found him hard to like, and kept away from him as a kindness to them both.

Meanwhile, Fracassus frolicked pettishly on the arboreal roof terrace of the Palace of the Golden Gates without an apparent care in the world. The sun shone, the orchards grew big with fruit trees, other towers sprouted all around without ever taking light from his, the servants brought whatever he desired, and only bouts of boredom – which he was unable to describe in words – cast a shadow on his happiness. Since he had no company his magnanimity was never tested, nor did he learn what it was to be mocked or teased. To relieve his feelings he sometimes pulled down the Lego edifices he’d built and threw the bricks off the roof. (Like Samson himself, Brightstar commented. A reference that was subsequently pulled when an editor pointed out who Samson was.) At other times Fracassus tore up the flowers in the flower beds, but no gardener dared remonstrate with him about that. All living things were his and he could rip at them as he liked. When he looked in the mirror he saw what his mother – when she was in the country – told him he was, namely a beautiful boy with a cherub’s complexion and spun gold hair from which he would be able to make whatever shape his ingenuity fancied.

CHAPTER 2

Concerning a father’s fears and a tutor’s skirt

But then the time came, as it must in the life of every child, gifted or not, to be removed from the condition of baby celebrity – where every burp and bubble is taken as an earnest sign of future greatness – to the obscure literalism of the schoolroom, where marks are awarded for performance and promise counts for nothing. Punching, biting, scratching and swearing, Fracassus descended from the roof terrace with its infinity pool, its sandpit, its swings and roundabouts, its giant television, its bar serving baby cocktails, hamburgers and candyfloss, and the constant attendance of reporters and photographers from Brightstar, to the classrooms of the lower Palace, to questions, comprehension tests, and words. For Fracassus this was a tailspin into darkest hell. Words! Until now he had whimpered, exclaimed, ejaculated, and whatever he had wanted had come to him on a golden platter amid praise and plaudits. So why, he wondered – or would have wondered had he possessed the words to wonder with – the necessity for change? The enormity of the shock, for any child, of having to go from pointing to naming cannot be exaggerated. But for Fracassus, for whom to wish was to be given, it was as catastrophic as birth. To have to find a word to supply a need is to admit the difference between the world and you. Fracassus knew of no such difference. The world had been his, to eat, to tear, to kick. He hadn’t had to name it. The world was him. Fracassus.

He had had no friends. He was the Prince. Princes proper have no friends. Jago had been too preoccupied in his search for self to be a brother to him. And in a sense he didn’t have parents either. The Grand Duchess, when she wasn’t travelling on business with the Grand Duke, was locked in her reading room, turning pages and letting her mind drift. Reading was an auditory experience for her. The leaves of her favourite novels fluttered between her fingers and as they did she could hear the wind blow through the enchanted forest. Sometimes she would turn only to turn back again, letting the pages sigh to her of danger then of rescue, rescue then of danger, back and forth. The books she loved best were printed on the finest paper, as diaphanous as fairy wings. They might float from her they were so slight. But when she snapped a volume shut she could hear the castle gates crash closed. Hush! She was alone. Wild beasts prowled. Who would come to her assistance now? Help, help!

For all his ambitions for his son, the Grand Duke was barely any better acquainted with him. He was too absorbed in his idea of Fracassus to notice him in actuality.

It’s also possible he was frightened of him. The boy’s uncanny, he sometimes thought. He lacks charm, he lacks looks, he lacks humour, he lacks quickness, he lacks companionableness, and yet he’s arrogant! He didn’t doubt that these absences would one day be the presences that got Fracassus noticed, but until then the Grand Duke had to find a way to live with him as a father. This he did by travelling overseas as often as he could.

There was talk on every floor of the Palace about the meaning of this parental dereliction. Some of the servants tried to be sorry for the boy but their pity foundered on some quality in him that repelled affection in any form. The word ‘obnoxious’ was starting to be whispered in the lifts. Nox was a far-off colony of the Republic that was seldom visited. Its inhabitants were reported to be querulous and slow-witted and to have small hands. People disliked for those or a host of other reasons were thought of as obnoxious – coming from Nox. Could that have been the real reason the Grand Duke and Duchess kept their distance – that they too thought of him as a visitant from Nox?

Hitherto, with no one listening or keeping an eye open, with no one prepared to doubt that his brain brewed extraordinary mental projects and that he spoke of them in arcane tongues to people unequipped to understand, the absence in him of the wherewithal to construct a sentence or progress a thought had gone unnoticed.

Until now.

The tutors into whose hands he’d suddenly fallen, like a god toppling from high estate into a fiery lake of devils, grasped the enormity of their task at once. Fracassus was not only short of words, he seemed to be in a sort of war with them. Had he only been surly they would have employed methods designed to relax him, make him feel safe, and communication would soon have followed. But he already was, in his surly way, communicative. He would answer their questions. He would sometimes even essay something in the nature of rough play, though he would immediately shrink should anyone play rough games back. The problem was that he seemed to feel he could get by well enough with the words he had and any attempt to teach him more was an attack upon him personally. Furthermore, he failed to see, since his tutors had words and they could do nothing better with their lives than teach

him, just exactly what words had to recommend them. Did he want to end up like them? He believed himself to be complete. Ineducable because there was nothing more he would need to know – and certainly nothing more these failures could ever teach him – for the life he intended to live.

‘You’re all prostitutes,’ he told them once.

And on another occasion, he called them ‘whores’.

They didn’t know whether to commend him for his loquacity – prostitute was the longest word they’d heard him use, and whore the most surprising – or discommend him for his misogyny.

As time went on and Fracassus’s education didn’t, his tutors acknowledged they were in a ticklish situation. They were paid handsomely to bring the boy up to scratch; alerting the Grand Duke and Duchess to the fact that scratch was still a long way beyond him would have been self-destructive. Whose fault, in that case, was that? Who but they could be to blame? The argument they prepared in their own defence, without accepting that there was anything to defend, went as follows:

Fracassus is an independent child with an original mind. His thoughts, we are pleased to report, are unhampered by that dependence on received opinion which we often see to be the price paid by those who are overly articulate, language-crammed or well read. Since words come to us infected by assumptions of which even the most self-conscious can remain unaware, the more disengaged from language a man is, the more connected to his own heart we can rely on him to be.

The chief architect of this argument had been Dr Cobalt, the only woman on the team of Fracassus’s tutors. A graduate of three universities and holding degrees in two soft subjects and one middlingly hard, Dr Cobalt was tall and slender like a snowy egret and made flustered men think longingly of the cool and even icy climates of the past. She had been the Grand Duke’s choice. Being masculinist by inclination – a hunter before he was strong enough to shoulder a rifle, a boxer before a glove tiny enough for his little fist could be found – Fracassus, his father believed, would surely benefit from contact with her gentler virtues. They all would. The Grand Duke, as evidenced by his taste in domestic architecture, was epithetical by nature. And everything about Yoni Cobalt suggested adjectives. She had long hair, big eyes, full breasts, and wore high heels. And every adjective cried out for an adverb. She had very long hair, very big eyes, very full breasts, and wore very high heels. That she could have been a very successful catwalk model or children’s television presenter made her decision to sacrifice herself to the bringing up of Fracassus the more estimable. Her senior on the tutorial staff, Dr Strowheim, commended her in moderation to the Grand Duke and Duchess, but repeated as though it were his own argument that their son was enriched by what he didn’t know.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights