- Home

- Howard Jacobson

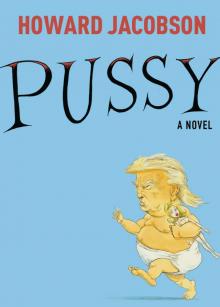

Pussy Page 15

Pussy Read online

Page 15

Fracassus emailed Philander under the table while his new wife was making her speech. Need you.

Accipio cum gaudio, Philander emailed back.

Caleb Hopsack stole a look at Fracassus’s phone. ‘Ordinary people are not going to be pleased with too much of that,’ Caleb Hopsack told him from the side of his mouth.

‘Then there’s your first job,’ Fracassus said. ‘You stop him.’

‘You’ve just started him.’

‘I know.’

Fracassus had hatched a plan. He was going to be an enigma.

Fracassus had not met Philander since the time he came down off the bus and told him to believe every word he said – that’s to say to disbelieve all of it – not because it was true but because it wasn’t. For his part, Philander had no memory of that meeting. ‘I forget everybody I meet,’ he confessed, when the two men got together at the Palace, ‘because I’m not interested in them.’

‘I am exactly the same,’ Fracassus said.

What he wanted Philander to do was organise buses to tour the Republics making promises that could never be kept, those being the sorts of promises the populace preferred. Philander flicked the hair out of his eyes and made a salute. ‘Roger,’ he said. Then he made a joke – ‘Mind you, I’m not promising.’

Fracassus, who had never got a joke, didn’t get this one. But he trusted Philander to let him down. In his eyes the campaign was now well and falsely up and running.

Artisanal Seven! Fracassus tweeted. Losers.

Hopsack texted his dissatisfaction. Public want action not insults.

Artisanal Seven! Fracassus texted. Chuck the losers out.

Not quite there yet, Hopsack tweeted. Something more definite required. Public wants assurances there won’t be more.

I will build a wall, Fracassus tweeted. And when I build a wall no one gets over it.

Better, Hopsack texted. But ‘no one gets in’ would be better still. ‘Over’ suggests athleticism and ordinary people like that. ‘In’ suggests invasion and ordinary people fear that.

But by that time the wall had gone viral. Build the wall! Build the wall! 20,000 people tweeted in ten minutes.

Sojjourner’s team tweeted that there already was a wall.

Oops! Fracassus retorted. They think they’ve got me. Well I’m gonna build a higher wall.

In another ten minutes another 20,000 tweeters. Build a higher wall! Build a higher wall!

Sojjourner was not above tweeting below the belt herself. Inanity can do as much damage as malignancy, she posted. And followed this with a caricature of Fracassus, Hopsack and Philander posing together in front of the Golden Gates. Money, imposture and humbug, she tweeted. The Three Wise Monkeys of Urbs-Ludus. Screw the Economy, Screw the People, Screw the Weather.

Fracassus couldn’t have been happier. The words Sojjourner used were too long. Inanity! Malignancy! Imposture! Whoever kept a friend, never mind won an election, saying ‘imposture’? He practised pronouncing it in front of a mirror, pouting his lips as though to kiss an old lady from the other side of the room. He looked forward to using it in the forthcoming television debate.

She accused him of profiteering, sexism, mendacity (another one), racism, incitement to hatred, isolationism, and bad spelling.

He accused her of inexperience, liberal elitism, political correctness, man-hating, minority mania, and softness on terrorism. She was not a person, he went on, to be trusted with her finger on the nuclear button. ‘Finger’ was the only word in that list that was his.

She accused him of not knowing that the Republics didn’t have a nuclear button.

I wouldn’t worry about that, Caleb Hopsack texted him to say. The Ordinary People’s Party have been campaigning to maintain our nuclear capability for years. They won’t want to be told we don’t have one.

Philander sent Fracassus an email from one of the neighbouring Republics, he wasn’t sure which. Confusion all confounded this end. Electorate don’t know what to think so I’m telling them not to think anything. Regarding nuclear button, press the young harridan on her ignorance of defence issues. Say there is button but only you know where to find it. Bonam fortunam.

She accused him of being in bed with the military.

He accused her of being in bed with no one.

Don’t go there, Hopsack texted.

Fracassus amended his tweet and accused her of wanting to be in bed with him.

No! Hopsack texted.

She accused him of toe-wrestling with foreign autocrats.

He accused her of xenophobia, a word Philander had emailed him.

Again no! Hopsack texted.

She accused him of putting the interests of his business empire before the interests of the country.

He accused her of confusing the country with her class and of giving succour to extremists. (Philander again.)

You’re falling into her trap, Hopsack texted. Stick to words of one syllable or she’ll pull you down with her.

Like Leander enticing Hero, Philander added by email.

Dr Cobalt entered the conversation, contesting that version of the myth. Hero swam to Leander of his own accord.

Professor Probrius agreed, but thought the story open to innumerable interpretations.

Start opening that door, Dr Cobalt argued, and there was no saying what moral and behavioural relativism wouldn’t amble through it next.

Losing plot, Hopsack texted. Get rid of those two.

Fracassus was surprised to discover himself sentimentally attached to his old tutors and fired them on the spot.

CHAPTER 28

A brief treatise on buffoonery

Much as Philander knew better than anyone that life was a sore trial and man’s tenure of it brief, he was still taken aback when he too was dismissed from Team Fracassus. Though Caleb Hopsack had always been against Philander’s appointment, he wasn’t the person directly responsible for the dismissal. Whichever way one looked at it, that person was Philander himself.

It began with a picture in a newspaper – it doesn’t matter which, since it appeared eventually in all of them – of two otters whose recent acquisition by Urbs-Ludus Zoo caused greater interest than it might otherwise have done on account of their extraordinary resemblance, both in body and in face, to Fracassus and Philander, after whom they were instantaneously named. In the photograph, the Fracassus otter had his head to one side, much as Fracassus would incline his whenever a subject beyond his comprehension arose and he wanted to show his disdain for it. Despite the reputation for cuteness enjoyed by the species, this otter showed his teeth in unexplained fury. When his mother saw the photograph it brought immediately to mind Fracassus’s expression the time he came into the bedroom she shared with her dear late husband, turned his mouth into a trumpet of hate, and said ‘Fuck, nigger, cunt.’ The other otter, forever to be known as Philander, possessed the original’s genius for looking at once serious and amused and delighting in his capacity to be both. He was carrying a fish in his mouth, boastfully, as though no other otter in the sea had ever fished as well as he had, and this too reminded people of Philander. The photograph was captioned Maccus and Fracassus – Maccus being a character in a popular children’s movie of long ago, a villain with a head resembling that of a hammerhead shark, and Fracassus being Fracassus.

Philander, being Philander, felt the need to go into print at once, firstly to show that he got the joke and enjoyed it, and secondly to discourse on the name Maccus which went back a lot further than The Pirates of the Caribbean, first appearing as the designate for a stock figure of ancient Roman farce, not to be confused with Buccus who, in Philander’s view, was funnier. Perhaps without his actually knowing it, the journalist responsible for the otter story had started a conversation about the nature of buffoonery as differently understood by the ancients and the moderns, indeed as bearing widely differing interpretations today. To note a resemblance between the Grand Duke Fracassus and him was inevitable given their close

political connection, and without doubt flattering to himself, bearing in mind his subordinate position. But while they were both buffoons, the buffoonery of the one was not to be confused with the buffoonery of the other. His own, if he would be permitted to say so, was entirely self-aware – an act of conscious self-disparagement aimed at puncturing his own and society’s pomposity and preventing people from confusing levity with falsehood – whereas Fracassus’s proceeded from too deep an engrossment in the cares of office for him to notice he was being ridiculous or be concerned about it. Where he, Philander, was the author of his own buffoonery, Fracassus was its victim. But let us not despair! The great Plato, it should never be forgotten, had abhorred a sense of humour in a ruler, by which logic, as a person entirely lacking in one, the Grand Duke Fracassus was a more natural leader, Platonically speaking, than he, Philander, would ever be.

Called to explain this, Philander pleaded loyalty. What else was he saying but that Fracassus was ideally suited for the role of solemn majesty that awaited him? But wriggle on the pinhead as he might, Philander stood accused of calling the man whose election he was meant to be working for a clown. And an inferior clown, at that, to his accuser. He had to go. Acta est fabula, he wrote in his goodbye email to Fracassus. The play is over – though it wasn’t so far over that Philander had no further part to play in it. Before the day was out he was working for Sojjourner Heminway.

CHAPTER 29

The speed of lies

Grievous as Philander’s defection might have been, it wasn’t. Nor was he the only recreant in the months leading up to the election. Of Fracassus’s original team, only Caleb Hopsack remained. Ideologically, Hopsack felt at one with Fracassus. The Grand Duke and the leader of the Ordinary People’s Party – it was a marriage of converging interests made in political-convenience heaven. Hopsack attended the Palace every morning, was photographed with or without Fracassus in front of the Golden Gates, and brought news from the remotest corners of the Republics. Good news and bad, though it was easy – as with the Philander affair – to confuse the two. It was Hopsack who, as a politician incapable of inspiring loyalty himself, best understood why the people loved those whom no one else could. Where the Sojjourner camp took comfort from the spectacle, as they saw it, of rats deserting a sinking ship, the populace saw a beleaguered leader betrayed by inferior men. Fracassus had promised to Muck Out the Pig-Pen. Well, these were the squeals the Pigs made when they resisted eviction. Rats, pigs – who needed them? The fewer influential followers Fracassus had, the more honourable they believed him to be. Other politicians could boast their lickspittles and cronies. Fracassus stood alone. His isolation proved his authenticity.

Authenticity became the word of the campaign. At least he says what he means, Hopsack’s people tweeted. And saying what one meant became more important than meaning what one said.

Sojjourner no sooner secured Philander’s services than she wished she hadn’t. What she’d hoped would be a public relations coup turned into its opposite. Was she so desperate that she needed Fracassus’s cast-offs? Was she so lacking in integrity herself that she was indifferent to its absence in others? Quick to see her mistake, she sent Philander to tour the remotest corners of the Republic on a bus, from which he made exactly the same speeches he’d made when he was working for Fracassus.

Otherwise, Sojjourner’s operation appeared to be on track. ‘Appeared to be’ in the sense that pollsters showed her enjoying a healthy lead over her opponent, no matter that her rallies were less populous and ecstatic. The website Brightstar, which had been on Fracassus’s side ever since his birth, read the polls as a Liberal conspiracy to keep Fracassus out and saw her unenthusiastic rallies as the true measure of her unpopularity. She was too dumpy to be liked, it said, too small to be seen, too shrill to be listened to, too cold to excite hope, too excitable to calm fears, too assertive to be womanly, too remote from the struggles of ordinary people, too close to a pampered elite, too ambitious, too pushy, too ready to play the woman card, though, frankly, anyone less like a woman … and much else in that vein.

If it didn’t say that she was too clever for her own good it was only because it didn’t want to invite comparisons with Fracassus, who was definitely clever enough for his.

With only a few weeks of the election left to run, Fracassus believed it was time to mention her trousers. Those trousers, he tweeted.

That jacket, Sojjourner’s people tweeted back.

But the trousers were more telling.

Professional commentators wondered if she’d turn up for the televised debate in a slit skirt and stilettos. There was little doubt that this would put Fracassus on the back foot. It was well known that a slit skirt could induce catalepsy in Fracassus. Only on the right woman, he tweeted, when this matter was raised publicly. Whatever his protestations, who could say, if Sojjourner were to wear a skirt, that Fracassus, guided by a power greater than himself, wouldn’t attempt to slide his hand under it?

Sojjourner scotched all such expectations in advance by insisting that while light entertainment, or whatever name he gave to groping women, might be his field of operations, serious politics was hers. Election watchers called this her first mistake of the night. At a stroke she took the fun out of the debate and showed that she was out of touch with the times. People, even of her class, had grown weary of gropee victimology. Frankly, no one cared where Fracassus put his hands. Her second mistake was to mention the glass ceiling. So what if no other woman in history had ever made it to be Prime Mover? People weren’t going to be gender-bullied into making her the first. Her third mistake was to invoke diversity, a concept interpreted by voters to mean people of every sexual orientation and colour but their own. To be white and straight in Urbs-Ludus, when Sojjourner was at the stump, was to feel neglected. Her fourth mistake was to use the word ‘imposture’, enabling Fracassus, who couldn’t believe his luck, to purse his lips in practised imitation of its prissiness and make as though to kiss an old lady from the far side of the room. Looking directly into camera he mouthed the words ‘Stop it!’, at one and the same time mocking his opponent’s verbosity and reminding viewers that it was he who owned the medium that fed their fantasies. Her fifth mistake, which could be said to encompass all the others, was to oppress viewers with her mastery of argument and comprehensive grasp of world affairs.

Watching on a television in Yoni Cobalt’s apartment, Kolskeggur Probrius savoured the delicious irony of it. In the days of the Great Purge of the Illuminati, Sojjourner Heminway had been one of the students instrumental in getting him removed from the university for demeaning those he taught by teaching them too well. Now here she was, falling foul of just such contempt for knowledge herself, only this time the judges were the common people not the privileged elite. The great purge of the purgers had begun.

Yoni Cobalt sat with her head in her hands all through the debate and kept them there as the first verdicts on the candidates’ performances were delivered.

‘I won’t say I told you so,’ Professor Probrius said. ‘But I did long ago predict that those who tell the stories run the world.’

‘Stories! What stories? He doesn’t have anything to tell.’

‘My love, that is the story.’

Thus, without saying a word, and in losing the debate by every known measure, Fracassus was deemed to have won it.

Greatest margin of victory in any televised debate in history, he tweeted.

And then again, an hour later, Time to send sad Sojjourner on a long jjourney.

CHAPTER 30

The end of days

It has been observed that mankind plays at life and only realises the seriousness of what it’s done when it’s too late.

In the days immediately preceding the election a baffled stillness fell on the Republics, and on Urbs-Ludus, the play capital, in particular. What, of all that had been said, did anybody mean?

There’d been a change of mood after the debate. Fracassus had won by not winning b

ut didn’t act or look like a winner in the days following. He oozed belligerence in his tweets, but on his person an unaccustomed softness could be discerned. Caleb Hopsack’s heart beat faster. He feared that Fracassus had suddenly developed an interior life, a dangerous black hole that could suck in self-doubt and second thoughts. Caleb Hopsack might have been a joke that only the smartest people got, but to himself he was certitude or he was nothing. Without it, the ground he walked on felt like the surging sea. There was terror in his tweets. Beware the backsliders, he tweeted, not just once but a hundred times. If the world slid back he would be the first to be engulfed. He pictured himself face down in the landslipped mud, where he would lie uncorrupted by change for 100,000 years until some fresh-faced archaeologist found him and wondered what function such a creature, strangely garbed and grimacing, could ever have performed.

Fracassus visited his mother in her chocolate factory and fairy room. She too thought there was something different about him. For a moment she even saw how it might be possible to like him. She asked him how his wife was handling the pressure. He looked bemused. He had forgotten he had a wife. He surprised her by enquiring about his brother. Had she heard from him recently? Normally he referred to Jago as ‘It’. Today Jago was his brother. It was a self-centred enquiry, but it was an enquiry all the same. Did he say anything about the election, he wondered. ‘I cannot lie to you,’ his mother said. ‘He will be voting for Sojjourner.’ She was surprised that Fracassus was not angered by this. ‘I don’t blame him,’ he said. ‘I’d do the same in his position.’

On his way out he tried guessing how many transpersons there were in the Republics. He reckoned he could afford to lose them all and still romp home a comfortable winner. But he didn’t tweet to say so.

Whatever had softened Fracassus, softened the populace. Not to the point of persuading those who hated Sojjourner to change their minds and vote for her. A change of mind is a rational decision and hatred of Sojjourner had nothing of reason in it. It was fed from wells of poison too deep to fathom. But it was as though belief in Fracassus began to blow away, like leaves that had only ever rested on him lightly. An hour before they’d been at the pantomime shouting ‘She’s behind you!’ Now that they were back out on the street it was as though the pantomime had been watched by someone else.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights