- Home

- Howard Jacobson

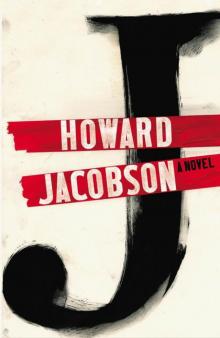

J Page 4

J Read online

Page 4

Well, my wife tells me so, anyway.

Or at least she does when she isn’t telling me the opposite. Phinny the Palaverous is how she refers to me to her girlfriends. Who know, of course, she doesn’t mean it.

I don’t say we fight. But we are not immune to malign influences beyond our kitchen and bedroom. How could we be? Are we not all one family?

That the dry, embittered colourlessness of the conceptual – to return to my theme – helped harden the nation’s heart is accepted as a truism by artists of today. Art wasn’t the cause or centre of the great desensitisation, for which, of course, all artists apologise, but WHAT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED – or TWITTERNACHT, as I like to call it when I am feeling skittish, by way of reference to . . . well to many things, one of them being the then prevailing mode of social interaction that facilitated, though can by no means be said to have provoked it – WHAT HAPPENED, IF IT HAPPENED, I say, happened, if it did, because as a people we’d anaesthetised the feeling parts of ourselves, first through the ugly liberties with form taken by modernism and second through the liberties taken with emotion by that same modernism in its ‘post’ form. I say ‘we’ because there is nothing to be achieved by saying ‘they’, indeed there is much to be lost, given that ‘they’ is a policed pronoun today, but when I am certain no one is looking (I mean this figuratively) I poke a finger at the alien intellectualism that brought such destruction first on itself and then, as an inevitable consequence, on all of us. Thus, again, the felicity of my TWITTERNACHT jeu d’esprit, twitter like much else in the same vein that was then the rage, having proceeded from the alien intelligences of the very people who were to lose most by it. Call that irony, a concept of which they, in particular, were overfond, which is an irony in itself. Let’s be clear: no one behaved well, but there is such a thing as provocation. The largest beast can be maddened by the smallest parasitic mite. (Especially when it’s clever . . . the mite, that is.) I will say no more than that.

Except . . . No, I’ll stick to my guns and shut up. ‘You talk too much,’ Demelza is always saying to me. And I’m a man who listens to his wife.

Perhaps future generations will describe what we do now as a cult of feeling, but better to feel than not to, better to experience love than its opposite. Better, in short, to live now than to have lived then. If the cost of not allowing ourselves to return to that inglorious past, or anything resembling it, is a certain mistrustfulness and vigilance, I happen to think it’s a price worth paying. Hence . . . well, hence my doing what I do. My ho humming, as the Divine Demelza calls it. I don’t spy on my students or my colleagues. I keep an eye open, that’s all. For what? Well, for anything or anyone – how can I best put this? – left over. For business dangerously unfinished. For matter out of place, as a famous anthropologist once described dirt. For recidivism. In any of its guises, recidivism is what we fear most. Hence a job of this sort falling to someone teaching at an art college. Because art, for all its adventuresomeness, is also capable of being the most recidivist of human activities, forever falling back in reaction to what was itself a reaction to something else. People can behave like savages when they are allowed to, but only in art do they go so far as to call themselves primitivists. And when the primitivist urge doesn’t seize them, the psychoaesthetic urge, the study of human evil – itself another form of primitivism, when you come to think about it – does. So portrait painting is a further recidivism that’s frowned on and discouraged – that’s in so far as one can discourage anything in a free society. In the main, prize-culture does the job for us. When all the gongs go to landscape, why would any aspiring artist waste his energies on the dull and relentless cruelties of the human face? While not wanting to affect modesty, I suspect I wouldn’t be enjoying the favour and seniority I do – I omitted to say that I am Professor Edward Everett Phineas Zermansky, FRSA – had I not from an early age followed nature’s laws in the matter of beauty. There are painters who paint more experimentally than I do, without doubt, but of my more troubled colleagues – those who still hanker secretly for the alien and the grotesque, even the degenerate (though they wouldn’t dream of pronouncing that term aloud) – I cannot think of one who hasn’t had to wait a long time to be given recognition, and even longer to be given tenure.

But to return to the point from which I began, and I don’t apologise for my vagrant style – ‘Keep up!’ I tell my students when I sense they are losing me; ‘Keep up!’ I even have to tell my wife on those occasions when I catch her glancing at her watch – I don’t claim more for what goes into my black folder on Kevern Cohen than it’s worth. I say ‘I keep an eye open’ but I do so only at the lowest level – code name Grey. Think of those I watch as birds, and I am no more than a Sunday twitcher. The work of serious, scientific ornithology is done by others. For which reason, while I am conscientious in my observations, I have never imagined that what I see or what I miss matters a great deal. Until now. Suddenly, I am conscious of having to deliver. It is as though the common house sparrow, on which – to nobody’s interest – I’ve been keeping an eye for some time, has overnight become an endangered species and I am at a stroke indispensable to the species’ protection. I won’t pretend to knowledge I don’t have. All my reports are now more scrupulously monitored than they were before, so I can’t say with any certainty that Kevern ‘Coco’ Cohen – one of the common house sparrows in question – has risen to the top of any pile. I have a feeling about him, that’s all. Or rather I have a feeling that they have a feeling. I like the man, I have to say. He has for several years been coming in one day a week to the academy, teaching the art of carving lovespoons out of a single piece of wood. I admire his work, which is exquisite, but there are some who find him a little too good to be true. Not the students; they love his air of grumpy probity as much as I love what he makes, and I am sure that when their opinions are canvassed they will speak of him only in the most glowing terms. But it goes against him with senior members of the college that he doesn’t drink with them, spends too much time in the restricted section of the library – not reading a great deal, according to Rozenwyn Feigenblat, our librarian, just staring into space the minute he is a page or two into what he does read, as though wondering what he came here for – and is rarely heard to apologise. I don’t, of course, mean for reading books, I mean for anything – an act of carelessness or forgetting, a brusqueness, a contradiction. The reason he gives is that as he lives on his own, works in isolation, and so rarely has occasion to lose his temper, he has nothing to apologise for. Not an argument well calculated to win him friends in the common room, because the truth is none of us really think we have anything to apologise for. But the way an institution works is that you go along with the prevailing fiction. And generally – if not individually – the habit of delivering brisk, catch-all apologies is much to be preferred to morbid memory which embalms the past in the Proustian fluids of the maudlin. (Though Proust is no longer read, we still retain the adjective.) My authority for this is the media philosopher Valerian Grossenberger, author of Seven Reasons To Say Sorry, whose series of daily lectures for National Radio some years ago can be said to have changed the way we all think. Modern societies had spent too much time, according to Grossenberger, rubbing the twin itches of recollection and penance. In the bad old days, ‘never forget’ was a guiding maxim – you couldn’t move, I’ve heard tell, for obelisks and mausoleums and other inordinately ugly monuments exhorting memory – but this led first to wholesale neuroticism and impotence and then, as was surely inevitable, to the great falling-out, if there was one. Rather than go on perpetuating the neurasthenic concept of victimisation, Grossenberger argued, the never-forgetters would have done better carving ‘I Forgive You’ on their stones. In return for which, we might have forgiven them. But that chance came and went. And now who, today, is going to forgive whom for what? Only by having everyone say sorry, without reference to what they are saying sorry for, can the concept of blame be eradicated, and guilt at las

t be anaesthetised.

Saying sorry, Grossenberger concluded, when he came to address the Bethesda Academy recently – an old man now, but still possessed of his silky powers of reasoning – releases us all from a recriminatory past into an unimpeachable future. We stood and applauded that, not least as it struck us that he was delivering a last eulogy to his own distinguished, emollient career. But if you ask me whether Kevern Cohen stood along with the rest of us, I have to say I don’t recall his being present.

I make nothing of it. He might indeed be a man who is so equable of temper that the idea of apology mystifies him. Or he might not yet have got past the ‘never forget’ stage in his own life. Let us hope that the latter is not the case and agree simply that he’s a queer one. ‘I find him weird,’ my wife said only the other day, after we’d had him over for dinner. ‘With those droopy eyes and all that hand washing and tap checking. It’s like having What’s-he-called over.’

‘Lady Macbeth?’

‘I said he.’

‘Pontius Pilate?’

‘Yes.’

‘As in that fine Dürer—’

‘Spare me the lecture, Phinny. Him, yes. But if he’s like this in our house, what must he be like in his own?’

‘Pontius Pilate?’

‘Kevern, you fool.’

‘Worse, I don’t doubt. Much worse.’

‘What I don’t understand is how he knows when to stop. While he was helping with the washing-up he kept wandering over to the stove to make sure the gas was off. “I’ve checked that,” I told him, but he said he feared he might have brushed against the taps when he was drying up and it was better to be safe than sorry. But at what point does he decide it’s safe?’

‘You should have asked him.’

‘I did. But his answer was unilluminating. “Never,” he said.’

‘Never?’

‘Never. Isn’t that terrible?’

‘Yes. But he has to stop sometimes. The man sleeps, for God’s sake.’

‘I asked him about that, too. Presumably you sleep, I said. So when do you call it a day? At what point are you able to close your eyes? And his answer to that was more unilluminating still. “When I can’t stand it any more,” he said. And how do you know when that is, I asked. “I just know,” he said.’

‘Maybe it’s when he gets tired. He has the air of a man who tires easily. Men do, you know.’

This irritated her. ‘And women don’t?’

Which irritated me. ‘Of course they do, but we aren’t talking about women,’ I snapped. ‘Or about you.’

We stared angrily into each other’s faces.

Why did she, I thought, have to bring her sex into everything?

Why did I, I saw her thinking, have to be so critical of her?

Why were her eyes, I thought, so quick to water up?

Why were mine, I knew she thought, so quickly fierce?

Why did I marry her, I wondered. What had I ever seen in that pallid skin and impertinently, stupidly, retroussé little nose? How could I stop myself, I wondered, from striking her?

Why did she accept me, the witterer I was, I heard her ask herself. How had she let those ugly crossed teeth of mine ever nibble at her breasts? Why had she ever allowed any part of me to come near any part of her? How much more would it take for her to strike me?

I slunk away.

She followed me into my studio.

I wondered if she was carrying a knife from the kitchen. The carver she’d recently had sharpened. I closed my eyes.

‘I’m sorry, Phinny,’ I heard her say.

I turned around abruptly. She started. Was she afraid of what I might be carrying? A trimming knife? My razor? A hammer?

‘Me too, Demelza,’ I said.

We were both sorry, and made love whimpering how sorry we were into each other’s ears. I kissed her lovely little nose. She gave me her breast to nibble. Sorry. Sorry. Sorry for what, exactly? Neither of us knew. But without doubt a baseless irascibility had begun to be a fact of our marriage. Had we fallen out of love? I didn’t think so. Friends of ours were reporting the same. A querulousness that appeared suddenly from nowhere and vanished just as inexplicably, though each time the period it took for lovingness to return extended itself a little more. We had a formulation for it: things just seemed to be getting on top of us. But why? Why, when we lacked for nothing, when beauty accompanied us wherever we went, when every source of discord had been removed?

It was shortly after this particular exchange of unpleasantries, anyway, that the file code for Kevern Cohen changed from grey to purple. Purple isn’t vermilion. We weren’t in danger territory. But others, I was now to understand, were reliant on what I knew as a sort of confirmation, let’s even say – to be plain about it – as a cognitive intensification, of what they knew or didn’t know themselves. Kevern Cohen was becoming a precious commodity.

THREE

The Four Ds

i

IT WAS AILINN who had been ringing him. Against her own instincts. But in line with her companion’s, though her companion thought she could go a little further and actually leave a message. ‘Even just a hello,’ she said.

‘When you know me better, Ez,’ Ailinn told her, ‘you will discover I am not the sort of woman who leaves hellos on men’s phones. They pick up or they lose me.’

‘And when you know me better,’ Ez told her, ‘you will discover I am not the sort of woman to egg people on to do what they don’t want to do. But this is different. You aren’t yourself. I’ve never seen you so down in the mouth.’

‘That’s because you haven’t seen me often. Down in the mouth is not what I do, it’s who I am.’

‘That isn’t true. You were hopeful when you met him. You said you thought you might just have met your soulmate.’

‘I did not!’

‘Well you said you thought you’d met someone you could possibly get on with.’

‘I think that’s rather different.’

Brittle-boned and careful with herself, a woman who seemed to Ailinn to quiver with mutuality, Ez leaned in very close. ‘Not for you it isn’t,’ she said, as though the strain for Ailinn of being Ailinn was sometimes more than she could bear for her. ‘A man has to be your soulmate before you’ll give him the time of day.’

Ailinn raised an eyebrow. She and Ez were not well enough acquainted, she thought, to be having this conversation. She wasn’t sure they were well enough acquainted for Ez to be bringing her tea in bed, fluffing up her pillows and patting her hand either, but she put that down to the older woman’s loneliness. And consideration, of course. But offering to know so much about the kind of person Ailinn was, her ways with men, what made her happy, when she was and wasn’t herself, the errands on which she sent her soul, for God’s sake – all that seemed to her, however kindly it was meant, to be a presumption too far.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights