- Home

- Howard Jacobson

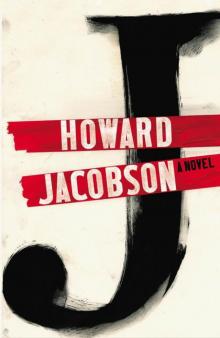

J Page 7

J Read online

Page 7

So he was lying. She didn’t judge him. If anything, it thrilled her to be a silent party to such delinquency. But it explained why he went to such lengths to protect his privacy. No one was ever going to come to so remote a place, so difficult of access, to steal a wardrobe; but what if it wasn’t thieves he feared but, she joked to herself, the Biedermeier police?

Once, although she hadn’t mentioned her suspicions, he explained that property wasn’t the reason he was careful.

‘Careful!’

‘Why, what word would you use?’

‘Obsessive? Compulsive? Disordered?’

He smiled. He was smiling a lot so she shouldn’t take fright. He liked her teasing and didn’t want it to stop.

‘Well, whatever the word, I do what I do because I hate the idea of . . . what was that other word you used once, to describe my lack of sexual attack? – invasion.’

‘I didn’t accuse you of lacking sexual attack.’

‘OK.’

‘I truly didn’t. I love the way it is between us.’

‘OK. Invasion, anyway, is a good word to describe what I fear. People thinking they can just burst in here, while I’m out or even while I’m in.’

‘I understand that,’ she said. ‘I am the same.’

‘Are you?’

‘I always locked my bedroom door when I was a little girl. Every time the wind blew or a tree scratched at my window I thought someone was trying to get in. To get back in, actually. To reclaim their space.’

‘I don’t follow. Why their space?’

‘I can’t explain. That was just how I felt. That I had wrongly taken possession of what wasn’t mine.’

There was something temporary about her, Kevern thought. Of no fixed abode. Tomorrow she could be gone.

A great wave of protectiveness – that protectiveness he knew he would feel for her when he first saw her and imagined rolling her in his rug – crashed over him. Unless it was possessiveness. Protectiveness, possessiveness – what difference? He wanted her protected because he wanted her to stay his. ‘Well you don’t have to feel that here,’ he said.

‘And I don’t,’ she said.

He kissed her brow. ‘Good. I want you to feel safe here. I want you to feel it’s yours.’

‘Given the precautions you take,’ she laughed, ‘I couldn’t feel safer. It’s a nice sensation – being barred and gated.’

But she didn’t tell him there was safe and safe. That all the barring and gating couldn’t secure her peace of mind. That she kept seeing the pig auctioneer, for example, who had known both their names.

‘Good,’ he said. ‘Then I’ll keep battening down the hatches.’

She laughed. ‘There’s a contradiction,’ she said, ‘in your saying you want me to think of your home as mine, when you protect it so fiercely.’

‘I’m not protecting it from you. I’m protecting it for you.’

This time she kissed him. ‘That’s gallant of you.’

‘I don’t say it to be gallant.’

‘You like me being here?’

‘I love you being here.’

‘But?’

‘There is no but. It’s not you I’m guarding against. I’ve invited you in. It’s the uninvited I dread. My parents were so terrified of people poking about in their lives that they jumped out of their skins whenever they heard footsteps outside. My father shooed away walkers who came anywhere near the cottage. He’d have cleared them off the cliffs if he could have. I’m the same.’

‘Anyone would think you have something to hide,’ she said skittishly, rubbing her hands down his chest.

He laughed. ‘I do. You.’

‘But you’re not hiding me. People know.’

‘Oh, I’m not hiding you from people.’

‘Then what?’

He thought about it. ‘Danger.’

‘What kind of danger?’

‘Oh, the usual. Death. Disease. Disappointment.’

She hugged her knees like a little girl on an awfully big adventure. In an older man’s bed. ‘The three Ds,’ she said with a little shiver, as though the awfully big adventure might just be a little too big for her.

‘Four, actually. Disgust.’

‘Whose disgust?’

‘I don’t know, just disgust.’

‘You fear I will disgust you?’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘You fear you will disgust me?’

‘I didn’t say that either.’

‘Then what are you saying? Disgust isn’t an entity that might creep in through your letter box. It isn’t out there, like some virus, to shut your doors and windows against.’

Wasn’t it?

It was anyway, he acknowledged, a strange word to have hit on. It answered to nothing he felt, or feared he might feel, for Ailinn. Or from Ailinn, come to that. So why had he used it?

He decided to make fun of himself. ‘You know me,’ he said. ‘I fear everything. Abstract nouns particularly. Disgust, despair, vehemence, vicissitude, ambidexterity. And I’m not just worried that they’ll come in through my letter box, but underneath the doors, and down the chimney, and out of the taps and electricity sockets, and in on the bottom of your shoes . . . Where are your shoes?’

She shook her head a dozen times, blinding him with her hair, then threw her arms around him. ‘You are the strangest man,’ she said. ‘I love you.’

‘I’m strange! Who is it round here who thinks trees are tapping at the window to reclaim what’s rightfully theirs?’

‘Then we make a good pair of crazies,’ she laughed, kissing his face before he could tell her he had never felt more whatever the opposite of disgust was for anyone in his life.

vi

Disgust.

His parents had once warned him against expressing it. He remembered the occasion. A girl he hadn’t liked had tried to kiss him on the way home from school. It was the style then among the boys to put their fingers down their throats when anything like that happened. Girls, it was important for them to pretend, made them sick, so they put on a dumb show of vomiting whenever one came near. Kevern was still doing it when he encountered his father standing at the door of his workshop, looking for him. He thought his father might be impressed by this expression of his son’s burgeoning manliness. Finger down the throat, ‘Ugh, ugh . . .’ Ecce homo!

When he explained why he was doing what he was doing his father slapped him across the face.

‘Don’t you ever!’ he said.

He thought at first that he meant don’t you ever kiss a girl. But it was the finger down the throat, the simulating of disgust he was never to repeat.

His mother, too, when she was told of it, repeated the warning. ‘Disgust is hateful,’ she said. ‘Don’t go near it. Your grandmother, God rest her soul, said that to me and I’m repeating it to you.’

‘I bet she didn’t say don’t put your fingers down your throat,’ Kevern said, still smarting from his father’s blow.

‘I’ll tell you precisely what she said. She said, “Disgust destroys you – avoid it at all costs.”’

‘I bet you’re making that up.’

‘I am not making it up. Those were her exact words. “Disgust destroys you.”’

‘Was this your mother or dad’s?’ He didn’t know why he asked that. Maybe to catch her out in a lie.

‘Mine. But it doesn’t matter who said it.’

Already she had exceeded her normal allowance of words to him.

Kevern had never met his grandparents on either side nor seen a photograph of them. They were rarely talked about. Now, at least, he had ‘disgust’ to go on. One of his grandmothers was a woman who had strong feelings about disgust. It wasn’t much but it was better than nothing. At the time he wasn’t in the mood to be taught a lesson from beyond the grave. But later he felt it filled the family canvas out a little. Disgust destroys you – he could start to picture her.

Thinking about it as he lay in Ailinn’s

arms, trying to understand why the word had popped out of his mouth unbidden, Kevern wondered whether what had disgusted his grandmother – and in all likelihood disgusted every member of the family – was the incestuous union her child had made. He saw her putting her fingers down her throat. Unless – he had no dates, dates had been expunged in his family – that union didn’t come about until after she’d died. In which case could it have been the incestuous union she had made herself?

Self-disgust, was it?

Well, she had reason.

But if his own mother’s account was accurate, his grandmother had said it was disgust that destroyed, not incest. Why inveigh against the judgement and not the crime? And why the fervency of the warning? What did she know of what disgust wrought?

Could it have been that she wasn’t a woman who felt disgust in all its destructive potency but a woman who inspired it? And who therefore knew its consequences from the standpoint of the victim?

Do not under any circumstances visit on others what you would not under any circumstances have them visit on you – was that the lesson his parents had wanted to inculcate in him? The reason you would not want it visited on you being that it was murderous.

This then, by such a reading, was his grandmother’s lesson: Be careful not to be on disgust’s receiving end. For whoever feels disgusted by you will destroy you.

Had he wanted to destroy the girl whose attempt to kiss him had been so upsetting that he had to pretend it turned his stomach? Maybe he had.

Kevern ‘Coco’ Cohen got out of bed and religiously blew the dust off Ailinn’s paper flowers.

How many men were there? Six hundred, seven hundred, more? She thought she ought to count. The numbers might matter one day. One at a time the men were led, each with his hands tied behind his back, into the marketplace of Medina, and there, one at a time, each with his hands tied behind his back, they were decapitated in the most matter-of-fact way – glory be to—! – their headless bodies tipped into a great trench that had been dug specially to accommodate them. What were the dimensions of the trench? She thought she ought to estimate it as accurately as she could. The dimensions might matter one day. The women, she noted coldly, were to be spared, some for slavery, some for concubinage. She had no preference. ‘I will choose tomorrow,’ she thought, ‘when it is too late.’ Grief the same. ‘I will sorrow tomorrow,’ she thought ‘when it is too late.’ But then what did she have to grieve for? History unmade itself as she watched. Nothing unjust or untoward had happened. It was all just another fantasy, another lie, another Masada complex. As it would be in Maidenek. As it would be in Magdeburg. She looked on in indifference as the trench overflowed with the blood that was nobody’s.

FOUR

R.I.P. Lowenna Morgenstern

i

AILINN KNEW EVEN less about her family.

Kevern thought that Ez, the fraught, angular woman with the tight frizzy hair who had brought her down to share the cottage in Paradise Valley, was her aunt, but she wasn’t.

‘No relative,’ Ailinn explained. ‘Not even a friend really. No, that’s unfair. She is a friend. But a very recent one. I only met her a few months before I came away, in a reading group.’

Reading groups were licensed. Because they were allowed access to books not otherwise available (not banned, just not available), readers had to demonstrate exceptionality of need – either specific scholastic need or, if it could be well argued for (and mere curiosity wasn’t an argument), general educational need. Kevern was impressed that Ailinn had been able to demonstrate one or the other. But she told him she had simply been able to pull a few strings, her adoptive mother being a teacher.

Books apart, this account of her relations with Ez explained to Kevern why she had made so little ceremony of introducing them. It was as though she had never been introduced to her herself. He was amazed by how anxious she could be one minute, and how devil-may-care the next. ‘And you threw in your lot with a woman you’d met in a reading group, just like that?’

‘Well, I’d hardly call it throwing in my lot. She offered me a room in a cottage she hadn’t ever seen herself, for as long or as short a time as I wanted it, in return for my company, and some help painting and gardening, and I could find no reason to say no. Why not? I liked her. We had a shared interest in reading. And there was nothing up there to keep me. And I reckoned I could sell my flowers just as well down here . . . probably better, as you get more tourists than we do, and . . . and of course there was you . . .’

‘You knew about me?’

‘My heart knew about you.’

Her arrhythmic heart.

He couldn’t tell how deep her teasing went. Did she truly think they were destined for each other? He would once have laughed at such an idea, but not now. Now, he too (so he hoped to God she wasn’t playing with his feelings) wanted to think they had all along been on converging trajectories. But no doubt, and with more reason, his parents had thought the same.

She had no memory of her parents – her actual parents – which made Kevern feel more protective of her still.

‘No letters? No photographs?’

She shook her head.

‘And you didn’t ask?’

‘Who would I have asked?’

‘Whoever was caring for you.’

She looked surprised by the idea that anyone had cared for her. He picked that up – perhaps because he wanted to think that no one had cared for her until he came along. ‘Someone must have been looking after you,’ he said.

‘Well I suppose the staff at the orphanage to begin with, though I have no memory of them either. Just a smell, like a hospital, of disinfectant. I was brought up by a smell. And after that Mairead, the local schoolteacher, and her husband Hendrie.’

‘And what did they smell of?’

She thought about it. ‘Stale Sunday afternoons.’

‘They’d been friends of your parents?’

She shook her head. ‘Didn’t know my parents. No one seems to have known them. Mairead told me when I was old enough to understand that she and Hendrie were unable to have children of their own and had been in touch with an orphanage outside Mernoc – a small town miles from anywhere except a prison and a convent – about adoption. When they were invited to visit, they saw me. They chose me like a stray puppy.’

She normally liked to say ‘like an orange’, but there was something about Kevern that made her think of strays.

‘I can understand why,’ he said, losing his fingers in the tangle of her hair.

She raised her face to him, like one of her own flowers. ‘Why?’

‘You know why.’

‘Tell me.’

‘Because to see you is to see no one else.’ He meant it.

‘Then it’s a pity you didn’t choose me first.’

‘Why – were they unkind to you?’

‘No, not at all. Just remote.’

‘Are they still alive?’

‘No. Or at least Mairead isn’t. Hendrie is in a care home. He has no knowledge of the world around him. Not that he ever had a lot.’

‘You didn’t like him?’

‘Not a great deal. He was a largely silent man who fished and played dominoes. I think he hit Mairead.’

‘And you?’

‘Occasionally. It wasn’t personal. Just something men did. Do. Towards the end, before they put him in a home, it got worse. He started to make remarks like “I owe you nothing”, and “You don’t belong here”, and would throw things at me. But his mind was going then.’

‘And you never found out where you did belong?’

‘I belonged in the Mernoc orphanage.’

‘I mean who put you there?’

She shrugged, showing him that his questioning had begun to weary her.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. Adding, ‘But you belong here now.’

ii

As a matter of course, she woke badly. Her eyes puffed, her hair matted, her skin twice its age. W

here had she been?

She wished she knew.

At first Kevern thought it was his fault. He’d been tossing and turning, perhaps, or snoring, or crying out in the night, stopping her sleeping. But she told him she had always been like this – not morning grumpiness but a sort of species desolation, as though opening her eyes on a world in which no one of her sort existed.

He pulled a face. ‘Thank you,’ he said.

‘You’re not yet the world I wake up to,’ she said. ‘It takes me a while to realise you’re there.’

‘So why such desolation?’ he wanted to know. ‘Where do you return from when you wake?’

‘If only I could tell you. If only I knew myself.’

Mernoc, Kevern guessed. He saw an icy orphanage, miles from nowhere. And Ailinn standing at the window, barefooted, staring into nothing, waiting for somebody to find her.

Pure melodrama. But much of life for Kevern was.

And thinking of her waiting to be found, while he was waiting to find, gave a beautiful symmetry to the love he felt for her.

Zoo Time

Zoo Time Pussy

Pussy The Dog's Last Walk

The Dog's Last Walk J

J Shylock Is My Name

Shylock Is My Name The Finkler Question

The Finkler Question The Mighty Walzer

The Mighty Walzer The Making of Henry

The Making of Henry Whatever it is, I Don't Like it

Whatever it is, I Don't Like it Who's Sorry Now?

Who's Sorry Now? Kalooki Nights

Kalooki Nights